Thomas F. Cooley is Richard R. West Dean and the Paganelli-Bull Professor of Economics at New York University Stern School of Business, as well as a professor of economics in the NYU Faculty of Arts and Science. He was appointed dean of NYU Stern in 2002. A respected economist, Cooley is a fellow of the Econometric Society, a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, fellow and former president of the Society for Economic Dynamics, and writes a weekly column on economic matters at Forbes.com. Cooley announced in December that he would be stepping down as dean and returning to research and the classroom at the close of the 2008-2009 academic year. |

Dean Cooley was interviewed in February by Joanne Hvala, associate dean, marketing and external relations.

Joanne Hvala: Throughout your tenure as dean, you’ve talked about business as the most important force for social change. What exactly do you mean by that and why is it so important to you?

Dean Thomas Cooley: It is important to me personally because I want to be engaged in an activity that I think of as contributing something to society; that is part of my mission in life. A lot of people think of business as solely the pursuit of personal gain. Personal gain is one element of the business world, but I prefer to view business as the most powerful institution for improving the well-being of people. The profit motive can be a powerful lever in moving investment, institutions, and governments into doing what is good and right for society. The whole of the emerging green economy is a case in point.

JH: How has Stern been leading the dialogue on the understanding of and solutions for the current economic and financial crisis?

TC: First of all, we can claim to be the intellectual home of people who foresaw the crisis and acted on their understanding – both Nouriel Roubini, a professor of economics here, and John Paulson (BS ’78), one of our alumni, are examples. More broadly, we are in the enviable position of having a superb research faculty whose work in creating knowledge is matched by a deep understanding of the institutional setting of business. Our faculty truly understands the interlocking nature of complex issues. Whether the subject is marketing, management, finance, or economics, our professors have a willingness to speak out and articulate views about policy in the world of business. I think that’s served us well in this crisis.

"A lot of people think of business as solely the pursuit of personal gain. Personal gain is one element of the business world, but I prefer to view business as the most powerful institution for improving the well-being of people." |

JH: Talk about the White Papers Project, which has been an extraordinary faculty response to the crisis.

TC: The White Papers Project (see article) came as a response not just to the crisis itself, but to the real need we had for clarity. I can’t begin to tell you how many media calls the School received as the crisis unfolded. People needed help in understanding what was happening, what had gone wrong, and what the possible solutions would be. It became clear that there is a deep need to address the failures of the regulatory system and the market imperfections that led to this crisis and that it was important for us to be proactive and try to play a role in shaping how policy responds. So, together with my colleague Ingo Walter, I articulated the view that it was important for us to do something and do it quickly. He and I convened a small group of people, and we had this idea of writing a series of white papers on what were initially 10 different topics. That was where it started. Soon it expanded to 18 topics under discussion by a group of more than 30 faculty members working together to address the issues and the policy prescriptions that we think make sense. A coalition of the faculty was willing to work collaboratively on one of these topics. Our goal was to be ready as the new administration came into power and began to rethink the important issues. We held a number of day-long meetings, with lots of back and forth and internal dialogue. The result is this book that we produced in record time, which contains, I think, some very good ideas. We started this conversation at the end of October and had a draft in place by the week after Thanksgiving, with a produced prepublication version distributed before the University closed in December. In an academic context, this is about as fast as I’ve ever seen a series of fresh ideas hammered out and brought to the public.

JH: One of the things you’ve talked about, especially in conjunction with the White Papers Project, is the value of an independent voice. Can you talk about the value of having that independent voice from an academic institution, especially in light of what’s going on in the world?

TC: One of the reasons that the public looks to us is that they can’t cut through the cacophony of sound-bites, interest groups, and partisanship. Society needs institutions that will step back and take a dispassionate, nonpartisan look at how things are working, especially in times of crisis. That’s one of the reasons we have universities. When I first took over as dean I wrote that we have a fiduciary duty to the truth. Institutions like ours are valuable because we can take a dispassionate view and look at the way the world works and think about the way the world ought to work, without the influence of politics or special interests.

JH: Last April, Stern completed the largest fundraising campaign in the School’s history, raising over $190 million. What have those resources enabled Stern to achieve?

TC: On the human capital side, resources have helped us to fund some 23 named professorships and a large number of endowed research fellowships. These are essential to attracting and retaining the very best scholars in the world, and we’ve been quite successful at building our faculty. We’ve hired more than 90 faculty members in the seven years I’ve been dean, which is a stunning infusion of talent. The resources have also helped to fund more scholarships for undergraduate students and for graduate programs that enable students to study abroad. We’ve also been on a major campaign to improve our physical space, which gets very heavy usage and constantly needs refurbishing – some areas hadn’t been touched for many decades. We poured a lot of resources into transforming it, and we’ve actually increased our total physical space by at least a third already.

JH: What are the advantages of the School’s location in New York City?

TC: I wouldn’t trade our facility and our location for the greatest building imaginable anywhere else. We’re in the heart of commerce in New York, and it’s a vibrant, diverse, exciting place. More important, we’ve used the city as an educational asset – both as a classroom and a laboratory – and it informs our research and teaching. We have access to a stunning array of practitioners who talk to our students about real work experiences. Our students are exposed not just to the world of banking, finance, and Wall Street, but to consulting firms, nonprofits, arts organizations – for instance, they learn how businesses like the Metropolitan Opera work and to understand luxury retailing. We take full advantage of an incredibly enriching environment.

"I think business education always faces a challenge when the economy goes through a cycle. ...One of the things this crisis teaches us is that business educators do have to think about how to teach people to have dynamic, forward-looking habits of thought, because a lot of business education is inherently backward-looking." |

JH: Looking more broadly, Stern has made some partnerships with schools and companies around the world. How have these global partnerships enhanced the School?

TC: Global business education is in great demand and we have been steadily building our global portfolio for the past eight or nine years. Our TRIUM program is one of the most sought-after executive education programs in the world. It’s enabled us to form great partnerships with two other outstanding schools, the London School of Economics and HEC Paris, and to attract and capture as part of the Stern alumni and student body an incredibly diverse set of senior managers from around the globe. We also have a new program with Hong Kong University of Science and Technology – a master’s program in global finance that’s helped to develop Stern’s reputation in Asia. We have two new programs coming online in Europe targeted at very specific areas of finance, which I think are badly needed programs. And we have developed executive programs for companies in India and elsewhere in the world.

JH: Stern admissions have set new records – our undergraduate SAT scores have never been higher and the selectivity of our graduate students has risen over the years. Why do you think Stern is a magnet for these bright and accomplished students?

TC: It’s always the quality of the faculty, the programs, and the experience that matters to students. Obviously, people care about reputation, and ours has soared, driven by improvements in the quality of our faculty and programs, and increases in the visibility of NYU as a very desirable destination university. But the other thing that I think is particularly telling is the quality of the student experience, beyond the education. We’ve worked very hard to build a sense of community and a positive experience for our students so that they’re really happy to be here and don’t see it as just something they’re doing for a while. And when they leave, they feel a connection that will continue for a long time. We know that from talking to our students and measuring their experience. It’s really an important part of the value proposition for Stern.

JH: What do you see as the major challenges facing business education today?

TC: I think business education always faces a challenge when the economy goes through a cycle. This is a particularly severe cycle, so the questions that people are going to raise are, “If something like this can happen, is it the fault of business education? Are we teaching people the right things? Do they leave here with the right kinds of values? Do they have the right kinds of tools?” One of the things this crisis teaches us is that business educators do have to think about how to teach people to have dynamic, forward-looking habits of thought, because a lot of business education is inherently backward-looking. Business is a dynamic social construct that has changed dramatically and is going to continue to change dramatically. The challenge is to give people the right analytical tools, and to teach them to be forward-looking and to know the right questions to ask. It’s not a static profession.

JH: As you reflect on your tenure as dean, what are you the proudest of?

TC: I’m most proud of how successfully we were able to work together as a team and how we were able to unite around a set of common goals and create a sense of community, pride, and confidence that we know what we’re doing, and we’re doing it well. I think we’ve really built the faculty and the student body and the administrative framework for the School in a way that has enhanced its reputation, and made it a wonderful place to be a student, an alum, a professor, or an administrator. I’m really proud of that!

JH: What’s been your most gratifying aspect of the job?

TC: The most gratifying aspects have been the incredible people I’ve gotten to meet and make friends with among our alumni and students and the sense of mutual respect and purpose that I feel. They’ve been wonderfully supportive, full of creative ideas, energy, enthusiasm, and astonishing accomplishment. I’ve had the opportunity to meet so many people who are successful in many, many dimensions. Having had the opportunity to lead such a dynamic and diverse institution has also been a personal growth experience for me.

JH: What have you enjoyed most about meeting the alumni, in particular?

TC: I’ve most enjoyed being able to go to alumni and say, “Here we are, we’re your school, we’re doing great things, and your success is something we’re proud of. Be engaged with us, be involved with us, and help us achieve this mission.” The responsiveness of our alumni to that message has just been extraordinary.

JH: Is there a particularly memorable moment of your deanship?

TC: I met an alumnus in India named Abraham George (MBA ’73, PhD ’75). I visited a school he was running for the children of the destitute in the countryside near Bangalore. I didn’t know Abraham George yet and I hadn’t been too well briefed on his school and his other efforts. It was a very moving experience to see what he was trying to accomplish. Here was an alumnus who had been enormously successful in business, who believed firmly in the business proposition and the value of markets and of education, and who was trying to transform, in his way, a part of society that has been left out. It was the ultimate embodiment of the proposition that business is an important force for social change. And, of course, Abraham has become a friend and his many children have become very important to me as well.

JH: What would you most like to see happen next for the School over the next five to 10 years?

TC: I would like to see the School become even more recognized as the intellectually lively go-to place that people look to for knowledge and insight about the world of business. Hopefully the School will continue to influence both policy and practice. We need to focus on thought leadership and community. I think that mission is more important than any particular programs. I am proud of the progress we have made, but there is much to be done. I am sure my successor will take on this challenge with enthusiasm.

JH: What’s next for you?

TC: My plan is to go back to teaching. I am going to take some time off, finish writing a book and other work, and spend a bit more time at the Council on Foreign Relations, but I will return to the faculty and be here to teach and to support whoever is leading the School next. I’ve invested so much here, and I feel so passionate about Stern. It is a wonderful institution.

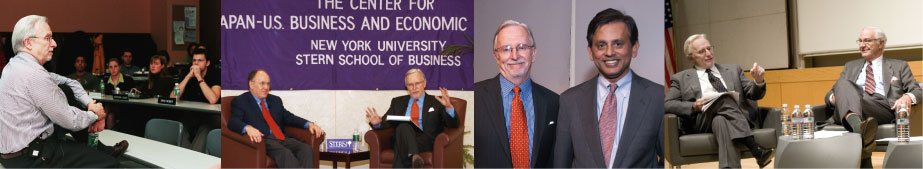

From left to right: Dean Cooley met with students at a Dean’s Roundtable luncheon; he discussed the global economy with his thesis advisor, Nobel Laureate Edward Prescott at a Japan-US Center event; he met with alumnus Abraham George at a student club event centered on India’s development; and he discussed how to fix the financial crisis with finance professor Roy Smith and a panel of experts from The Economist and the Council on Foreign Relations. |

![]()