Stepping into the Shoes of a Cosmetic Giant

By Daniel Gross

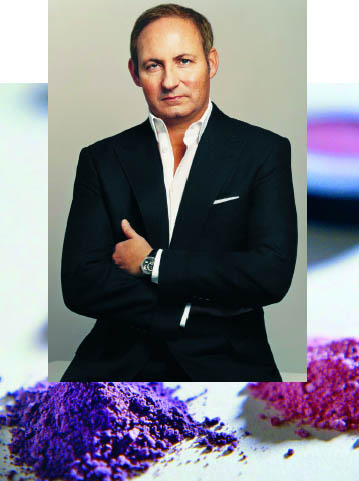

It can be a daunting challenge for a non-family member to assume responsibility for a third-generation family company – especially when your bailiwick includes running the firm’s namesake brand. That’s the task John Demsey (MBA ’82) faces as global president of the Estée Lauder Brand.

It can be a daunting challenge for a non-family member to assume responsibility for a third-generation family company – especially when your bailiwick includes running the firm’s namesake brand. That’s the task John Demsey (MBA ’82) faces as global president of the Estée Lauder Brand.

The Estée Lauder brand is the heart of the eponymous cosmetics company, founded by Estée Lauder in 1946. While Estée Lauder died in 2004 at the age of 95, the third generation of family leadership – her grandson, William Lauder, is president and chief executive officer of the company, son Leonard Lauder is the chairman, daughter-in-law Evelyn Lauder is senior corporate vice president, and granddaughter Aerin is the senior vice president, global creative directions of the Estée Lauder brand – carries on the tradition.

Demsey grew up in Shaker Heights, Ohio, attended Stanford University, and went to work at Macy’s after graduation. He parted paths from most of his Stern colleagues in the class of 1982 by forgoing a career in investment banking and returning to retail, working at Bloomingdale’s, Saks, and Revlon before joining Estée Lauder in 1991 as the vice president of sales for the West Coast region.

At the time, the firm was privately held and relied on a few large, powerful brands. Today, Estée Lauder is a publicly traded multinational organization (2005 revenues were more than $6.3 billion) with operations in 130 countries and more than 22,000 employees. The company has an impressive portfolio of brands – Estée Lauder, Origins, Clinique, M·A·C, Bobbi Brown, Donna Karan, etc. – that may seem to compete with each other. “The corporation is run as a portfolio of different brands with unique, dedicated brand management and creative direction,” said Demsey. “Our philosophy is that we would rather own our competition than compete with somebody else.”

In 1998, Demsey was named the head of one of those brands – M·A·C. He built it into a $500 million business, and developed the M·A·C AIDS fund into a major fundraising force. “Companies at the end of the day are about people, they’re not just about products, numbers, and cash flow,” said Demsey. “When you can engage people toward a common goal, or raise awareness about issues, it creates a richer environment.” Demsey also said that the Lauder family’s personal philanthropic activities in areas such as the arts and breast cancer were one of the things that attracted him to the company. “When I joined M·A·C, I saw the work that was being done with AIDS as an incredible opportunity to make a difference.” In addition to his current responsibilities with the Estée Lauder brand, Demsey still runs M·A·C.

For Demsey, the value of the Stern MBA has been in the thought process it has instilled. “It gives you a context of how to think, and how to gather the information and work as a business leader. Having the flexibility, business savvy, and sometimes the street smarts to integrate all of this is what separates you from your competition.”

His advice for those just starting out in the industry or looking to transition into it: “Do what you like.” And be willing to work on the periphery of businesses you're interested in. With fashion or cosmetics, he noted, there are “all sorts of ways to get into the game” – in advertising, publishing, retail, and management consulting. “Sometimes you might be better served by not going directly into the industry but by gaining your experience doing something else.”

Having celebrated its 60th birthday in March 2006, Estée Lauder – like most other well-known brands – faces challenges. In the US, the waves of consolidation and the decline of traditional department stores continually disrupt established sales channels. Internationally, “we're working to redefine the brand's regional relevance, particularly in Asia. International experience is extraordinarily important and probably the most valuable thing I've learned over the last 10 years,” he said. “Take India and China for example. This is where we're all going to now in terms of how products go to market. If you can get international experience, it’s definitely something that will serve you well. It matters a lot now, and it’s going to matter even more in the future.”

Demsey believes that for all that has changed in the global cosmetic industry, crucial aspects of the company’s culture, philosophy, and brands haven’t changed. The strategy for future success relies in part on looking backward. “We’ve really gone back to the DNA and the things that made the brand a success.” That means emphasizing, for example, the skin care for which Estée Lauder herself was so well-known.

And success means continuing to develop new product lines to appeal to new generations. Demsey worked on the development of the Sean Jean Unforgivable fragrance for men business with hip-hop impresario and entrepreneur Sean “Diddy” Combs. The company recently teamed with former Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent designer Tom Ford on the Tom Ford Estée Lauder Collection, a re-interpretation of select iconic Estée Lauder products. This fall, the team will launch the TOM FORD beauty brand.

The challenge of maintaining an established brand amid tough competition, while continually introducing new ones, may seem enormously complicated. But according to Demsey, at root, it’s rather simple. “At the end of the day you win by having the right product at the right price at the right time.”

Little Kids Bring Big Business

By Stephanie Sampiere

At age 37, Andy Stenzler (MBA ’94) recently launched his fifth business. But the idea didn't come from a fellow Stern graduate, or from the bankers and venture capitalists he got to know while building the restaurant chain Cosi. It came from a source closer to him – his wife, Shari Misher Stenzler (Tisch MA ’94). Shari had a hectic music class experience with their first child, Kylie, which led the couple to create Kidville, New York City’s first urban campus for kids.

At age 37, Andy Stenzler (MBA ’94) recently launched his fifth business. But the idea didn't come from a fellow Stern graduate, or from the bankers and venture capitalists he got to know while building the restaurant chain Cosi. It came from a source closer to him – his wife, Shari Misher Stenzler (Tisch MA ’94). Shari had a hectic music class experience with their first child, Kylie, which led the couple to create Kidville, New York City’s first urban campus for kids.

In Manhattan’s cul-de-sac-less, concrete jungle, parents of small children continually seek ways to escape with their children from confining apartments. Kidville’s first location, on the Upper East Side, caters to the area’s more than 15,000 kids under the age of 5. With class names like “Big Muscles for Little Babies,” “From Bach to Rock,” and “My Big Messy Art Class,” Kidville is a one-stop shop for the one-month to five set, offering music, gym, and art classes, as well as a place for kids and parents to mingle, shop, and eat.

The Stenzlers found that parents were looking for a single place that has all types of classes for their children, so that they don't have to travel to different places for art, gym, and dance. Kidville took this idea and added additional services for parents who arrive early or have time after class, such as a café for lunch and snacks, a retail store for buying birthday gifts and toys, and a salon for kids’ haircuts and moms’ manicures.

The Stenzlers found that parents were looking for a single place that has all types of classes for their children, so that they don't have to travel to different places for art, gym, and dance. Kidville took this idea and added additional services for parents who arrive early or have time after class, such as a café for lunch and snacks, a retail store for buying birthday gifts and toys, and a salon for kids’ haircuts and moms’ manicures.

“Certainly there are a lot of competitors in this space,” Stenzlersaid. “But typically those competitors are either a music guy, a danceguy, or a gym guy, and I think before we came along, nobody had grasped whatparents really want.”

The parents have responded. In the year-plus that Kidville has been open, it has attracted more than 3,000 members, most of whom live between 60th and 96th Streets on Manhattan’s east side. While Stenzler says that moms attend the majority of Kidville classes, dads also try to make them, as do a fair share of nannies.

“We’ve become a real community,” said Stenzler. “Youcan’t choose when your friends have kids, so you have to make new friendsthat have kids the same age. That’s one of the powers of Kidville. It hasbecome a community for moms to meet, dads to meet, and the nannies to meet.”

Andy Stenzler celebrates with his wife, Shari, and their children, Kylie and Colby. |

Kidville also offers New York City’s largest pre-school alternative program. Kidville University is a gradual separation program that allows children to start classes with their parents and then socialize with other children and learn through different types of play. In the past year, the class has grown from 20 to 105 students.

Kidville University, along with the other Kidville programming, was developed by the Stenzlers, along with help from Andy’s mom. Iris Stenzler was a New York City public school teacher and day camp owner for more than 40 years. After she retired, she became an informal advisor for Kidville, but missed the day-to-day interaction with children and came on board full-time as an administrative advisor.

In addition to the Stenzler family, Kidville was founded by two families close to NYU. Laurie Tisch, Honorary Chair of the Children’s Museum of Manhattan, and Liz and Emanuel Stern, Leonard Stern’s son and daughter-in-law, are investors in the business. So, too, is Rammy Harwood, current NYU Stern Langone student and a former partner in Stenzler’s earlier business, Cosi. Tennis stars Andre Agassi and Steffi Graff, and Richard Chapman and Gordon Hamm, owners of Garage Management Corp., are also investors in Kidville.

Speaking about his time at Stern, Stenzler described how he was able to complete the Langone Program on an accelerated pace because of his lucrative first job selling commercial air conditioners at York International. “I was taking nine credits a semester at Stern while I was working, and I got out in two and a half years, with the first class that graduated from the new building (the Henry Kaufman Management Center).”

Stenzler started Xando the year he graduated. Xando later acquired Cosi, assumed the Cosi name, and went public. He also has been involved in the founding of GTN.com, an online training company, and was the head of SoLofts, a sister real-estate initiative to CitiHabitats. Most recently, Stenzler teamed with fellow NYU Stern alumnus, Kenny Lao (MBA ’04) to launch Rickshaw, a fast-casual dumpling restaurant. (See STERNbusiness, Fall/Winter 2005)

In offering advice to other potential entrepreneurs, Stenzler said: “Take as many risks as you possibly can. A lot of students at Stern are married or have young children, and it’s hard to take a risk, but you have to find ways. There are ways to do it.”

So what’s next for the serial entrepreneur? In May, Kidville will tap into the 15,000 kids on the Upper West Side. Stenzler also sees Kidville expanding into a media company with DVDs and books on the way. But for now, he is content heading to work with his wife and two kids in tow. The rest is just gravy.

1. What has been the biggest change in the league and in the business of basketball since you bought the team in 1993?

When I bought the team, there was much more upside in ticket prices and local television revenue. Now, the big upside is going to be from selling out your building, selling sponsorships. Eventually, in the next five or six years, the upside will come in the big increase in national television revenue, the use of the NBA in different channels such as the Internet, and revenue derived from other parts of the world.

2. Forbes says the Rockets have appreciated in value nearly five-fold since you bought the team, from about $75 million to $420 million. Are basketball teams good investments?

Yes. The nice thing about sports teams is the lack of volatility on the downside. You won’t see a basketball team worth $420 million one year fall to $350 million the next year. Ultimately, we’re in a content business, and we produce a lot of shows – exhibition games, regular season, and playoffs – every year. What’s more, our sport seems to lend itself to global audiences in a way that, for example, baseball doesn't.

3. Every business in every industry wants to get in on the Chinese market. Is that why you signed Yao Ming, the first Chinese player in the NBA?

It was a basketball decision, pure and simple. We had the first pick, and I just wanted the player I thought could lead me to a championship more quickly. You have to remember that the NBA has very strict limitations on what teams can do outside their own boundaries. Most of what we can do in China revolves around signage in our own arena. That said, our profile in China is very high. There are millions of fans there who live, breathe, and die with the Houston Rockets.

4. Yao Ming’s new long-term contract means he accounts for 25 percent of the salary cap. Does it make you nervous to have so much of your payroll tied up in one player?

Sure it does. And Tracy McGrady has about 30 percent of it. And right now, both of them are injured, and we’re suffering. We’re not winning. My two best players aren’t playing. You have to take tremendous risks to win, and this is part of the business. This is another big difference between basketball and baseball, or football. Every player on my team is 20 percent of my starting team.

5. The Rockets won the NBA Championship twice in your early days of running the team. What are the challenges in repeating, especially with the salary cap?

In basketball, you can’t just sign whoever you want to sign. We have a salary cap. And we have a limit that says no single player can get more than 25 to 30 percent of the salary cap, depending on the years of service. That makes it much more equal for all teams, regardless of the size of your home market. I’m thrilled that we have this kind of structure in place, and that's one of the reasons the teams go up in value so much.

6. Other than winning a championship, what financial or performance metrics do you use to determine whether the team had a successful season?

Winning the championship is the only metric I care about.

7. You’re a well-known supporter of animal rights. How do you integrate your interests in these areas into your management of the Rockets? Can the two spheres mix?

I’m on the Board of the Humane Society. We give them free signage in our arena and free radio time. There are no animal products at our merchandise stores in the arena. And if you look at the menus in my restaurants, there’s no veal and no foie gras. I used to be a vegetarian, and I try to eat as little meat as possible. Our concession stands do sell hot dogs, and, of course, the balls are leather. I hear negative things about it once in awhile. But people appreciate it.

8. You were a large and early investor in First Marblehead Corp., which is in the student-loan business. Why did you think that was an attractive business? And have you been surprised at its growth?

Well, I met the people. And probably three-quarters of the success of a business are the people, not the product. You could see that there was going to be a future in private lending to students, because the government was not going to provide enough. But it took a long time. I invested in this company in the early 1990’s, and there were a lot of lean years until it went public in 2004.

![]()