When CEOs win coveted awards, it’s not necessarily good

news for shareholders – or for the CEOs themselves.

By James B. Wade, Joseph F. Porac, Timothy G. Pollock, and Scott D. Graffin

ILLUSTRATION BY GORDON STUDER

t is often difficult to determine whether a firm's performance is driven by the excellence of its top management team or by general economic and organizational conditions. After all, today's good fortune could result from a favorable industry environment or from the foresight of past managers who have since left. Conversely, uncontrollable economic downturns or deteriorated conditions inherited from predecessors may lead to disappointing performances. And how should such dynamics affect executive compensation? After all, in today’s environment, investors, analysts, and regulators like the Securities and Exchange Commission are all focusing on the size, content, and disclosure of executive compensation.

t is often difficult to determine whether a firm's performance is driven by the excellence of its top management team or by general economic and organizational conditions. After all, today's good fortune could result from a favorable industry environment or from the foresight of past managers who have since left. Conversely, uncontrollable economic downturns or deteriorated conditions inherited from predecessors may lead to disappointing performances. And how should such dynamics affect executive compensation? After all, in today’s environment, investors, analysts, and regulators like the Securities and Exchange Commission are all focusing on the size, content, and disclosure of executive compensation.

Organizational research suggests that social devices are often invented by third parties to assess the abilities of actors by creating a competency ordering. The media play an important role in constructing such orderings through certification contests, like Fortune’s Most Admired list, US News and World Report’s business school rankings, Institutional Investor’s all-star analyst teams, or Financial World’s CEO of the Year award.

But does it matter? Do the stocks of companies with all-star CEOs perform better than those of other companies? Or does CEO star status bring with it negative consequences for firms, such as managerial overconfidence and hubris? Do CEOs who top the lists receive greater compensation than their colleagues who don’t make the final cut? Or, as former NYU Stern Professor Charles Fombrun has suggested, can being named a star create the “burden of celebrity,” under which high expectations about future performance can lead to disappointment?

Testing Hypotheses

| “Do stocks of companies with all-star CEOs perform better than those of other companies? Or does CEO star status bring with it negative consequences for firms, such as managerial overconfidence and hubris?” |

We set out to examine these questions by constructing several hypotheses and testing them against a data set.

There’s good reason to believe that employing a star CEO could be valuable to a firm. As Fombrun has noted, having a highly recognized CEO at the helm may reassure stakeholders that the firm's future prospects are bright and, in turn, enhance the ability to attract higher quality employees, increase leverage over suppliers, and gain better access to needed capital. Certification awarded by experts would seem to confer a positive institutional reputation and lead to increased prestige power for the anointed star. That influence in turn may allow CEOs to leverage their knowledge and skills more effectively and produce positive firm outcomes. So our first hypothesis (Hypothesis 1) holds that: CEO certifications will be positively associated with a firm’s future performance.

On the other hand, CEO certification could theoretically be detrimental to future firm performance by inducing overconfidence and hubris in CEOs anointed as stars. CEOs who have been successful in the past may overestimate the expected returns from their corporate investment decisions, and may engage in expensive corporate acquisitions. Evidence suggests that overly confident CEOs are more likely to invest in “pet projects” funded by internal cash flows. This leads to an alternative hypothesis (Hypothesis 1a): CEO certifications will be negatively associated with a firm's future performance.

second set of hypotheses deals with compensation. According to executive compensation expert Graef Crystal, many corporate boards believe that high pay for star CEOs is a wise investment in managerial talent. Stakeholders may heavily weigh the outcomes of certification contests when evaluating a CEO’s talent because they are likely to be perceived as one of the few relatively neutral sources of information. Certified CEOs may thus be able to leverage their high-status in negotiating future compensation contracts with the board, or board members may simply feel justified in paying star CEOs more. We therefore hypothesize (Hypothesis 2): CEO certifications will be positively associated with CEO compensation.

second set of hypotheses deals with compensation. According to executive compensation expert Graef Crystal, many corporate boards believe that high pay for star CEOs is a wise investment in managerial talent. Stakeholders may heavily weigh the outcomes of certification contests when evaluating a CEO’s talent because they are likely to be perceived as one of the few relatively neutral sources of information. Certified CEOs may thus be able to leverage their high-status in negotiating future compensation contracts with the board, or board members may simply feel justified in paying star CEOs more. We therefore hypothesize (Hypothesis 2): CEO certifications will be positively associated with CEO compensation.

If subsequent firm performance is high after a CEO has been publicly recognized as competent, these earlier attributions will be reinforced, and the certified CEO may obtain a compensation premium. But if things go poorly, such CEOs may actually be held more responsible and receive lower compensation than non-certified CEOs whose firms achieve similar levels of performance. Being recognized as a star CEO may thus be a double-edged sword. That leads to our final hypothesis (Hypothesis 3): Certifications in the past will be positively associated with a CEO’s compensation when the firm's subsequent performance is high and negatively associated with his or her compensation when the firm's subsequent performance is poor.

CEO of the Year

We set out to test these hypotheses by examining performance and compensation figures from companies in the S&P 500 and companies whose leaders were named in Financial World’s CEO of the Year competitions. Each year, from 1975 to 1996, the magazine surveyed over 1,000 peer CEOs and business analysts, who rated between two and three thousand CEOs on criteria such as company performance, the ability to increase competitive position, leadership team and employee morale, and contributions to the industry, community, and nation at large. In each industry, analysts and CEOs selected three bronze medal award winners. The bronze medalists in each industry were then grouped within 12 general business categories. Research directors at Wall Street’s largest investment houses selected silver medal award winners for each category. Finally, the editors of Financial World chose the single gold medal award winner from among the silver medalists.

We set out to test these hypotheses by examining performance and compensation figures from companies in the S&P 500 and companies whose leaders were named in Financial World’s CEO of the Year competitions. Each year, from 1975 to 1996, the magazine surveyed over 1,000 peer CEOs and business analysts, who rated between two and three thousand CEOs on criteria such as company performance, the ability to increase competitive position, leadership team and employee morale, and contributions to the industry, community, and nation at large. In each industry, analysts and CEOs selected three bronze medal award winners. The bronze medalists in each industry were then grouped within 12 general business categories. Research directors at Wall Street’s largest investment houses selected silver medal award winners for each category. Finally, the editors of Financial World chose the single gold medal award winner from among the silver medalists.

Our sample included 278 companies that were members of the S&P 500 at the end of 1992, ranging in size from $154 million to $351 billion in total assets. (We began our sample in 1992 because that was when the SEC significantly increased its reporting requirements to require firms to report all elements of a CEO’s compensation.) We gathered panel data for the five years starting in 1992 and ending in 1996. The list of medal winning CEOs in our sample contains many of the most well-known and respected CEOs in the US, including Jack Welch of General Electric and Lawrence Bossidy of Honeywell.

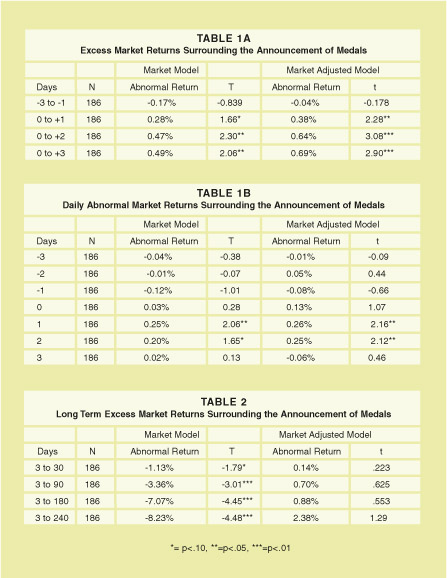

First, we assessed the immediate reaction of firm certification on performance. If investors believe that winning a medal conveys new information about the quality of the CEO and his/her ability to positively influence the future cash flows of the firm, one would expect a positive stock market reaction in the days following the announcement. Using either a financial market model or a market index, we calculated expected returns for each firm, and then subtracted the expected returns from actual returns. These differences are known as excess (unexpected) returns and reflect the extent to which the event provided new information about the value of the firm. We examined the impact of winning a medal on a firm’s excess returns in the days immediately following the announcement of the medal. As Table 1A shows, the excess returns in the three days prior to the announcement of the awards (days -3 to -1) were not significant. But after the announcement, the stock market reacted positively. The cumulative excess returns calculated using both the market model and market adjusted returns are positive and significant for the intervals from zero to two days and zero to three days. The daily excess returns before and after the event, (Table 1B) were positive and significant one day after the event using both the market model and market adjusted returns. Overall, our results suggest these awards are viewed favorably by the market, as Hypothesis 1 suggests.

To investigate the longer term effects of certification, we ran additional event studies over longer windows (Table 2). Using the market model, we found in the 30-day window that the cumulative excess return becomes negative and marginally significant. By 240 days, the return increases to -8.23 percent and is highly significant. Combined, these results suggest that while the immediate effect of winning a medal is positive, over time this trend reverses and becomes negative, as Hypothesis 2 suggests.

Compensation

Next, we looked into the relationship between CEO star status and compensation. We gathered data on compensation from the EXECOMP database. A CEO’s total direct compensation included salary, bonus, the value of restricted stock grants, options granted during the year, long-term incentive payouts that year, and all other types of cash compensation paid in that year. When we ran the tests, we found that winning a medal in the current year increases a CEO’s pay by approximately 10 percent and each medal awarded in the previous five years adds almost 5 percent to his/her total pay. We also tested Hypothesis 3 by interacting medals won in the past with firm performance as measured by return on common equity, a measure commonly used as a basis for awarding incentive pay. The interaction was highly significant and in the expected positive direction. Winning medals had a positive effect on a CEO’s pay when accounting performance was above zero but a negative effect when it was less than zero.

learly, being certified had a positive effect on the recipient’s compensation, over and above any performance differences that might exist between winners and non-winners. If a CEO’s compensation partially reflects the extent to which a company’s directors value a CEO’s abilities and contributions, this result suggests that certification does indeed heighten the tendency of boards to attribute special competencies to the CEO. It appears from our data that this attribution then leads the board to set up an evaluative “gauntlet” for the CEO in subsequent years, since certification has a positive impact on compensation as long as return on equity remains positive. If a company achieves a negative return on equity, star CEOs receive lower total compensation than non-medal winning CEOs for an equivalent level of performance.

learly, being certified had a positive effect on the recipient’s compensation, over and above any performance differences that might exist between winners and non-winners. If a CEO’s compensation partially reflects the extent to which a company’s directors value a CEO’s abilities and contributions, this result suggests that certification does indeed heighten the tendency of boards to attribute special competencies to the CEO. It appears from our data that this attribution then leads the board to set up an evaluative “gauntlet” for the CEO in subsequent years, since certification has a positive impact on compensation as long as return on equity remains positive. If a company achieves a negative return on equity, star CEOs receive lower total compensation than non-medal winning CEOs for an equivalent level of performance.

| “Investors initially bid up the price of company stock after learning about a CEO medal. However, shortly afterward they reverse course and bid down the price.” |

This general pattern of results suggests a more nuanced representation of the effects of CEO certification on firm and individual outcomes than is suggested by our original hypotheses and the prior research literature. Our results indicate that profitability is insensitive to CEO certification, at least over the one-year time window that we used in our analyses. If CEO certification has no short-term effect on the profitability of a company, then winning a medal can only be, at best, a noisy signal regarding the relationship between managerial ability and longer term profitability. And yet our results indicate that investors respond immediately, and over the course of the year, to this signal in predictable ways. Investors initially bid up the price of company stock after learning about a CEO medal. However, shortly afterward, they reverse course and bid the price down. Company boards seem to respond quickly to CEO certification as well, as our results on compensation show.

One possible explanation for this more nuanced pattern of data is that certification does indeed create a burden of celebrity. Simply maintaining a certain level of performance may not be sufficient for shareholders of firms with celebrity CEOs. Firms that employ star CEOs seem to have a higher expectational hurdle to meet in order to be valued positively by the market. While boards of directors seem to be more lenient in their expectations, they do respond more negatively to lower profitability when a star CEO is involved.

Overall, our results provide cautionary information for corporate pay policies. Given that CEO certifications do not appear to have a short-term beneficial effect on future profitability, the argument that boards of directors should pay exorbitant levels of compensation to attract and retain star CEOs whose firms have performed well in the past may be somewhat misplaced. However, boards of directors might be able to mitigate these costs by making pay more dependent on future performance. Ironically, the overconfidence that past success creates may provide a mechanism through which boards can clamp down on future compensation if a star CEO fails to deliver.

James B. Wade is associate professor of management and human resources at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, JOSEPH F. PORAC is George Daly Professor in Business Leadership at NYU Stern, TIMOTHY G. POLLOCK is associate professor of management and organization development at Pennsylvania State University's Smeal College of Business Administration, and SCOTT D. GRAFFIN is a PhD candidate in management and human resources at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

This research will be appearing in an upcoming issue of the Academy of Management Journal

![]()