A new book argues that the origins of American financial dominance can be traced to

a bold decision to close the New York Stock Exchange for more than four months.

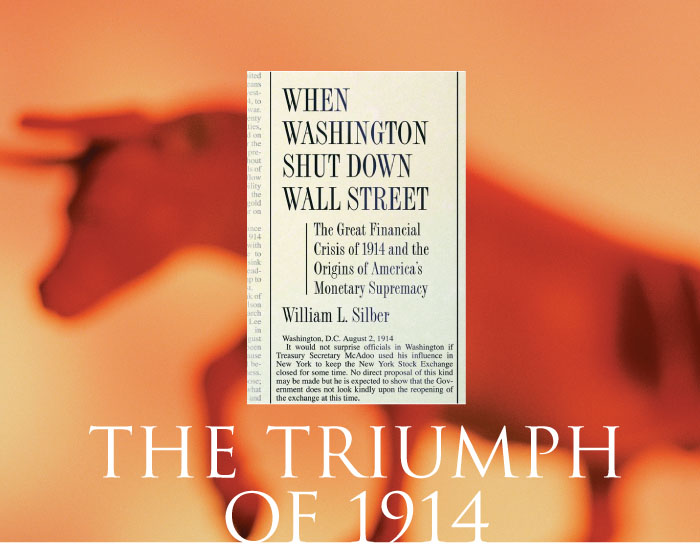

William Silber, the Marcus Nadler Professor of Finance and Economics and director of the Glucksman Institute for Research in Securities Markets at NYU Stern, has long been a popular and influential teacher and researcher. His new book, When Washington Shut Down Wall Street: The Great Financial Crisis of 1914 and the Origins of America’s Monetary Supremacy (Princeton University Press), documents an extraordinary and little-remembered episode. In the summer of 1914, Treasury Secretary William McAdoo was forced to respond to the financial crisis created by the outbreak of World War I. Working in something of a vacuum – the Federal Reserve, America’s central bank, was not yet operating – McAdoo orchestrated a series of controversial actions that helped insulate the United States from a major external shock, and, in relatively short order, engineered a way for the markets to reopen. In this episode, Silber finds the origins of America’s emergence as a financial powerhouse – and important lessons for crisis management.

He discussed his book with Sternbusiness.

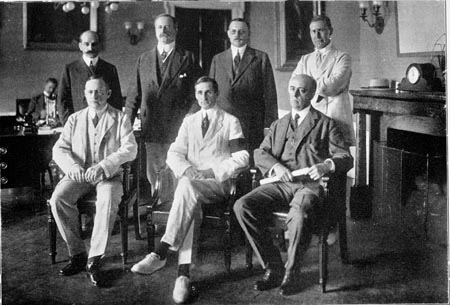

The Federal Reserve Board as they took office on August 10, 1914. From left to right, standing: Paul M. Warburg, John Skelton Williams (Comptroller of the Currency), W.P. G. Harding, Adolph C. Miller; Seated: Charles S. Hamlin (Governor), William G. McAdoo (Chairman), and Frederic A. Delano. McAdoo is wearing a mourning armband to commemorate the death, four days earlier, of his mother-in-law, Ellen Axson Wilson. |

Sternbusiness: How did you become interested in this topic?

Silber: There’s a puzzle that surrounds World War I. The New York Stock Exchange closed for four and one-half months, which is much longer than any other closure in stock exchange history. During the October 1929 crash, it closed for only two days, and that was to catch up on paperwork. In March of 1933, when President Roosevelt closed the banking system for eight days, the stock exchange also closed for eight days.

The conventional explanation has been that the stock exchange was closed to prevent a collapse in stock prices. But that doesn’t make any sense. There was something else happening in the summer of 1914: the US was establishing the Federal Reserve System. And there is some connection between the two events. The United States was on the gold standard. As the war started, foreign investors who had huge holdings of US stocks and bonds were starting to sell their securities and demand gold in exchange. But the Federal Reserve needed gold to establish the regional Federal Reserve banks and to create a new currency.

SB: So the exchange was closed primarily to stop the outflow of gold?

Silber: There were two choices confronting Treasury Secretary McAdoo. He could have suspended the US from the gold standard, which every European country had done by the first week of August, except for Britain. Or he could have kept the US on the gold standard. That required enacting some protective measures to ensure that gold would stay in the country. So on July 31, he closed the stock exchange, which prevented European investors from liquidating their holdings and exchanging them for gold. The decision was presented to the public as having been made by the New York Stock Exchange’s board of governors.

SB: Why was the US so committed to remaining on the gold standard?

Silber: This was about the credibility of America’s obligations. McAdoo was a pragmatist, not a philosopher. He followed his instincts that we should stay on gold, and I think he understood the potential gains. At that point, only the world’s financial superpower – Britain – remained on the gold standard. In part, this was viewed as an opportunity for the US – and the dollar – to seize financial leadership. The banker Henry Lee Higginson wrote President Woodrow Wilson in August 1914: “I repeat that this is our chance to take first place.”

SB: Closing the exchange stopped the bleeding. But there was still the potential for a domestic run on capital; people wishing to exchange bank notes for gold. How did McAdoo deal with that?

| “Wilson did not think poorly of McAdoo; quite the opposite. In March 1914, McAdoo, seven years younger than the president and a widower with grown children, became engaged to the president's daughter, Eleanor, 25 years younger than McAdoo. Wilson wrote to his intimate friend and confidante, Mary Ellen Hulbert, in Paris: “Dearest friend, has the cable brought you news of Nellie's engagement to Mr. McAdoo, the Secretary of the Treasury? Of course it has. That is what the Paris edition of the Herald is for. The dear girl is the apple of my eye: no man is good enough for her. But McAdoo comes as near being so as any man could. I am therefore content, not that she is to leave us for him, but that she should have such prospects for happiness.” |

|

Silber: Remember, there was no central bank. But McAdoo had another emergency weapon. Seven years earlier, in 1907, banks suffered terrible runs. Legislation passed in 1908 allowed banks to issue currency without gold backing. McAdoo convinced Congress to quickly pass a law in August 1914 that gave banks permission to issue their own currency. It was designed to plug the gap until the Federal Reserve System could get up and running. So he pushed out this new currency to prevent a run on the banking system.

SB: He had a unique background and a unique relationship with his boss – the President of the United States.

Silber: McAdoo was an entrepreneur. He was the president of the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad Company, which built the tubes connecting Manhattan and Hoboken; they’re operated by PATH today. He was socially conscious: in 1908 he insisted that women hired by the company be paid equal wages. He worked on Wilson’s 1912 presidential campaign. Wilson named him Treasury Secretary in 1913. And in March 1914, he became engaged to Wilson’s daughter. So the president was also his soon-to-be father-in-law. (see box at right)

SB: You refer to the closing of the NYSE as a tourniquet that stopped the bleeding. How did McAdoo cure the patient?

Silber: I think he recognized the need to get rid of these capital controls quickly. The underlying problem was the potential for gold to be exported in large quantities. So he had to figure out a way to bring gold back in. Within a couple of weeks, he organized the Bureau of War Risk Insurance – which would ensure shipping cargos against loss due to war activities. He thought that would stimulate an increase in US agricultural exports like cotton, which would generate gold inflows. The combination of measures worked and allowed the New York Stock Exchange to reopen on December 12.

What others are saying:

Floyd Norris, The New York Times:

It would now be heresy to suggest that a country could gain international stature by closing its capital markets for a prolonged time, but an insightful new book by William L. Silber, an economist at New York University, argues that the closing of the New York Stock Exchange at the outbreak of World War I played a critical role...

The conventional view was that the exchange was closed to keep share prices from plunging. But the book, When Washington Shut Down Wall Street, asserts that historians – and contemporary observers – had it wrong. …

By delaying the reopening of Wall Street and making sure that American grain was ready to be exported to Europe to bring in gold, the United States was able to stay on the gold standard and become an alternative to London as a financial capital. By late 1915, Britain and France were borrowing money in New York, denominated in dollars.

Carlos Lozada, The Washington Post:

In his fascinating work of financial history, When Washington Shut Down Wall Street, William L. Silber recounts the heroics of Treasury Secretary William McAdoo, who closed the New York Stock Exchange for more than four months – four months! – in 1914 to avert a larger economic crisis. European powers had begun to sell off their US stock holdings and convert their dollars into gold, which they shipped back home to finance World War I. But rather than let the desperate Europeans force the United States off the gold standard, the Treasury secretary brandished the NYSE “like a sledgehammer” against the gold drain and simply shut down the exchange. It was, as Silber explains, “a brilliant exercise of arbitrary power that helped propel the United States toward global financial supremacy.” |

|

SB: Wasn’t the long shut-down enormously disruptive to the stock business and New York generally?

Silber: This was a big deal. One of the reasons it could stay closed for four months was that a market in stock trading sprang up in the street, right next to the stock exchange, on New Street. And they literally traded stock in the street. McAdoo didn’t shut it down. First, it was a safety net. If people can trade, they’re not going to be screaming and yelling. And it confirmed that stock prices would not have collapsed. I was able to find newspaper clippings that mentioned prices on this black-market exchange. And since it was a cash market, it was difficult for European investors to sell here.

SB: He also helped bail out New York, right?

Silber: Indeed. McAdoo introduced the “too big to fail” doctrine. New York City owed the British huge amounts of securities that were denominated in pounds, and had to be paid off in pounds or gold in a matter of months. After meeting with bankers, led by J.P. Morgan, Jr., a bail-out was constructed whereby the banks issued dollar-denominated notes and helped manage the payment of existing securities.

SB: Shutting down trading, imposing capital controls, and allowing banks to freely issue currency sounds like a recipe for large-scale dislocation and inflation. Why didn’t that happen in this case?

Silber: A few reasons. Between August and October, national bank notes outstanding nearly doubled, and total currency outstanding grew by about 10 percent. But there was a huge precautionary demand for cash, and interest rates rose from 3 percent to 6 percent on prime commercial paper, which helped tamp down inflation. Then the exports of cotton began to bring gold flows back in, which relieved pressure on the dollar. Most important, McAdoo had an exit plan. If he did not have an exit plan, there would have been inflationary pressures.

SB: You argue that this episode proved an important economic and financial milestone for the United States. Why?

Silber: In the summer and fall of 1914, America established its credibility in terms of the dollar. Before 1914, the dollar wasn’t even an also-ran currency. Nobody cared about it. The two leading contenders for leadership behind the British pound were the German mark and the French franc. But when the dollar stayed on gold, that put the dollar in a monetary superpower category. By January of 1915, New York had already replaced London as a key global moneylender. But the real measure of a financial power is when you’re the international currency. At the end of the first World War, the world was still using the pound as an international currency. Britain went off the gold standard in 1919, and while it met its promise to return to the gold standard in 1925, it was too late. The dollar had become a really creditworthy currency. The dollar was a creditable alternative because, in the fall of 1914, it was shown that you could count on it when you couldn’t count on anything else.

SB: What are some lessons contemporary central bankers might learn from McAdoo?

Silber: I really like the tourniquet analogy. You have to stop the hemorrhaging immediately. Then you have to repair the wound. And then you have to restore normal function by sticking to an exit plan. You can’t be afraid to use emergency weapons.

SB: How does McAdoo stack up historically among American financial policymakers?

Silber: Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan (BS ’48, MA ’50, PhD ’77) in 1987, Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, and President of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York William McDonough, and the whole team after 9/11 get very high marks for crisis management. But they did it with an operational Federal Reserve System. McAdoo did it by the seat of his pants. And he went on to have a distinguished career: he was the Federal Reserve chairman, a candidate for president in 1920 and 1924, and a senator from California in the 1930s. As far as great Treasury secretaries go, I’d put him right up there behind Alexander Hamilton.

![]()