History provides crucial lessons

on how developed economies

have evolved into growth machines.

By George David Smith, Richard

Sylla, and Robert E. Wright

For most of its existence,

humanity neither enjoyed nor understood society’s capacity

for creating wealth and economic growth. Prior to the 18th

century, incomes generally hovered near the subsistence level.

To paraphrase the 17th-century English philosopher Thomas

Hobbes, human life was solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and

short. In the late 18th century, the English economist Thomas

Robert Malthus warned that the mass of humanity was doomed

to a life at the margins of starvation, as surges of population

growth would inevitably outstrip the finite sources of food

supply.

Things began to change in the 17th and

18th centuries, when people in Holland and Britain began

to produce a little more each year. As the gains added up

over time, modern economic growth had arrived. We define

economic growth as increases in aggregate real income per

person, (that is, income adjusted for inflation). For our

purposes, economic growth starts with the Industrial Revolution,

which began in the British Isles and spread from northwestern

Europe to new areas – North

America, parts of central and southern Europe, Scandinavia,

and, late in the 19th century, to the frontier “European” societies

of Australia and New Zealand, to parts of Eastern Europe and

Imperial Russia, and finally, to Japan, the only non-western

society to develop before the mid-20th century. In the late

20th century, the diffusion of industrialization spread rapidly

to the “dragons” of the Pacific Rim: Taiwan, Hong

Kong, South Korea, and Singapore, and then to the former communist

countries of Eastern Europe.

Today, several important

areas, including China, India, and Eastern Europe, seem poised

to experience sustained economic growth as well. And yet

most of the world’s

population remains poor, earning less than the equivalent

of $2 per person per day. Vast areas, including much of Africa,

Latin America, Central Asia, the Middle East, and Micronesia,

remain mired in grinding poverty, as the gap between the

richest and poorest societies continues to increase.

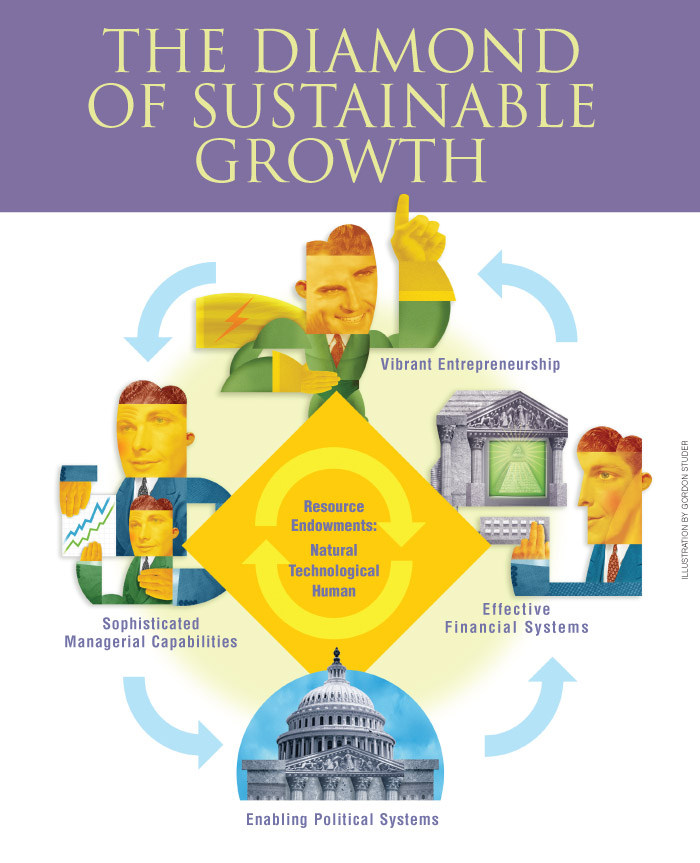

What accounts for such

differences? Many analysts focus on issues like culture,

natural resources, climate, and political systems to explain

the vast differences in economic experiences. But we believe

the answer lies in the intensely historical origins of economic

growth. History shows that over time, healthy, sustainable

economies possess four dynamic, human-made factors: (1) political

systems geared to enabling economic growth, (2) an effective

financial system, (3) vibrant entrepreneurship, and (4) sophisticated

managerial capabilities. In our model, each of these critical

factors is represented as a corner of “the

growth diamond.” As the illustration suggests, each of

the factors interacts with the others dynamically (and over

time). Proceeding counterclockwise from political systems to

managerial capabilities, each of the facets of the diamond

depends on the robustness of the preceding factors.

Growth Diamond

An effective political system enables economic growth, first

and foremost, by establishing a government that can unify

an economically relevant territory, establish order, and

protect the lives, liberty, and property of its citizens

through an impartial rule of law. A government must be able

to provide defense, address market failures, and ensure broad-based

access to education. Finally governments, over time, have

to address social and wealth inequalities so that they do

not undermine the social consensus and political stability

required to sustain broad-based economic growth.

"History shows

that over time, healthy, sustainable economies possess

four dynamic, human-made factors: (1) political systems

geared to enabling economic growth, (2) an effective

financial system, (3) vibrant entrepreneurship, and (4)

sophisticated managerial capabilities." |

On top of the political

system, a developing society must create a financial system

capable of transferring funds where they are in surplus to

projects where funds are needed. The institutional components

of a modern financial system include banks, capital markets,

and corporations – legal

entities that can borrow and issue ownership shares while

limiting the liabilities of their owners. Through insurance,

diversification, and hedging strategies, corporations also

substantially reduce the risks of entrepreneurial investment

while organizing production and distribution systems on

a large scale.

As enabling governments and financial systems grow strong,

they enhance the prospects for entrepreneurial activity. And

as the economic historian Joseph Schumpeter observed, entrepreneurship

enhances growth by introducing new products or services, opening

new markets, and creating new combinations of land, labor,

and capital. If government does not legitimize economic innovation

and provide a legal foundation for securing property rights

and reducing risks, entrepreneurs cannot thrive. Likewise,

if financial systems are inefficient, the costs of investment

in new projects can be prohibitive.

Finally, as new enterprises grow, they

rely on more sophisticated methods of coordination and control.

Sophisticated management (the coordination of complex organizations)

is predicated on robust education and is essential to any

society’s ability

to realize economies of scale and economies of scope, both

of which help bring down costs. Management also enables enterprises

to plan for the future, to adjust to changing market conditions,

and to invest in new, large projects.

The growth diamond can be applied to every society on earth.

The poorest almost never established enabling political systems,

if only because their governments abused, suppressed, or robbed

their citizens. Poor, but not destitute, societies never established

financial systems or created conditions for entrepreneurship

to flourish, often because their governments restricted economic

liberty or failed to secure property rights adequately. Many

societies that were able to achieve middling income may have

achieved some measure of progress in all corners of the diamond

temporarily but were not able to sustain their gains.

Early Examples

The Netherlands, the first nation

in modern history to develop the four elements of the growth

diamond, was also the first to experience sustained economic

growth. By the 17th century the Netherlands was a thriving

commercial society populated with what later generations

would call a broad-based bourgeoisie, or middle class.

The Dutch then lacked the technologies that would power

the Industrial Revolution from the late 18th century onward.

But the people of the Netherlands were relatively free

to pursue their economic self-interests under the protection

of a government that saw itself not as the country’s

owner, but rather as the people’s employee. The citizens

(note the change from “subjects”) of the Netherlands

willingly paid the world’s highest per-capita taxes because

they could see that tax revenues were spent on public goods,

such as defense and the country’s extensive network of

windmill-driven water pumps and dikes, and not on lavish parties

and castles.

The Dutch also managed

to create a representative form of government that did

not descend easily into tyranny. While certainly not perfect,

the government of the Netherlands provided the kind of

political foundation on which financial systems, entrepreneurship,

and management could anchor. The Dutch formed what historians

recognize as the first modern financial system – an

interconnected network composed of private banks and insurance

companies, a proto central bank, and securities markets

for public debt instruments, foreign exchange, commercial

paper, and corporate equities. Entrepreneurs blossomed,

finding it relatively easy and cheap to obtain financing

for an impressive array of business projects – from

domestic canals to shipbuilding to tulip horticulture.

As some of those businesses grew and matured, they became

too big and complex for the original entrepreneurs to handle,

so a class of specialized administrators developed to run

the larger business organizations.

Great Britain became the next nation

to develop a robust growth diamond. The British would lead

the world into the Industrial Revolution – the era of machine-driven, factory-based

mass production. Again, the formation of a non-predatory government

that looked unlikely to slide into tyranny was a prerequisite.

It came in the wake of 1688, when the British Parliament replaced

the royalist Stuart monarchy with a Dutch prince who would

be checked by the will of Parliament and bound by laws as interpreted

by an independent judiciary – the first modern constitutional

monarchy.

The British shrewdly borrowed best

practices from more economically advanced societies. Soon

after the Glorious Revolution, Dutch-style financial institutions

and markets arose in Britain. Not long after, British entrepreneurs

began a vast array of new enterprises that led directly

to revolutions in agriculture, transportation, and manufacturing.

People with highly developed management skills emerged,

making new strides in efficiency. Based on superior institutions

in public finance, new mass production industries, and

organizational capabilities, Britain transformed from a

peripheral island racked by political instability into

the planet’s most potent economic and military force.

In the 18th century,

Britain remained highly mercantilist, enacting tariffs

and other policies that it thought would enrich the home

islands at the expense of its colonies and enemies. But

in the 19th century, political economists such as David

Ricardo and John Stuart Mill elaborated on Adam Smith’s

critique of protectionism, which helped Britain to enact pro-growth

policies, including free trade and anti-slavery legislation

by the mid-19th century. The British continued to extend their

empire until it was said that the sun never set upon it.

A Colony Rises

Britain’s relatively prosperous North American colonies,

chafing under imperial restrictions on their economies, would

eventually outstrip Britain as the world’s leading economy

after establishing their own growth diamond. Here, again, government

took the lead. Suffused with myriad checks and balances – three

branches of government, property protections, political and

economic liberties, and protections for minority rights – the

US constitution formed the core of an enabling political system.

Soon after its ratification, the rest of the country’s

growth diamond crystallized.

"A

great lesson that economic history teaches us is that

when it comes to developing a healthy private sector,

the public sector serves as the crucial foundation, and

financial systems matter – both in fostering entrepreneurship

and supporting the efficient managerial systems that

any society needs to sustain growth over the long term." |

Just a few years after the

new government took effect, Americans enjoyed a financial

system that included a monetary unit (the US dollar), a central

bank (the Bank of the United States), and a growing number

of private commercial banks and insurers. As in the Netherlands

and Britain, the financial system unleashed the forces of “creative destruction” by

linking investors to entrepreneurs with good business ideas.

Canals and turnpikes appeared, connecting the frontier

to the major seaports, which encouraged American farmers

to look for ways to grow more wheat and raise more livestock

so that they could enjoy more manufactured goods. Later,

railroad and telegraph systems emerged and, in just a few

decades, sprawled across the continent in a dense network.

The sheer size of the United States, along with its distance

from potential enemies, conferred enormous advantages for its

economic development. The enormous size of the American market

by the late 19th century also enabled firms to grow to enormous

scale, as capital-intensive industries and retail businesses

in particular drove down costs and prices while driving up

demand, resulting in the creation of ever more businesses,

small and large, local and national.

Railroad managers helped

develop the tools of modern management – concepts

like cost accounting, managerial accountability, fixed versus

variable costs, and corporate structure. Those tools, in turn,

made possible the great industrial corporations of the late

19th and early 20th centuries. To some degree, the large corporation – embodied

in companies like Standard Oil, General Motors, and DuPont,

replaced the “invisible hand” of the laissez-faire

market with the “visible hand” of coordinated management.

Looking Back

By World War I, the rich societies that

had successfully built growth diamonds had evolved further

into open access economies – ones

that provided reasonably widespread economic opportunity

and encouraged competition. Open access economies provided

for social mobility based relatively more on merit rather

than birthright. They sought to educate everyone and to reduce

discrimination. They also kept the costs of entry into and

exit out of markets low. At any given time, small-, medium-,

and large-sized companies tended to co-exist, each challenging

the others to greater efficiency and quality.

Today, economists, politicians, and

development professionals continue to seek ideas for crafting

policies that will enable long-suffering poor countries to

join the developed world. As they do so, they would be well-advised

to keep the growth diamond in mind. Of course, it does not

explain everything. Such factors as geography, climate, war,

demographics, disease, culture, and changing technological

and competitive environments, to name a few, matter greatly.

Yet a great lesson that economic history teaches us is that

when it comes to developing a healthy private sector, the

public sector serves as the crucial foundation, and financial

systems matter – both in fostering entrepreneurship

and supporting the efficient managerial systems that any society

needs to sustain growth over the long term.

Governments are vital

for economic growth, but they can also keep societies in

poverty. Once the government is right – not

predatory, and not overly prone to caving in to special interests – the

other factors of the economic growth diamond can turn ideas

into marketable goods. Many new business projects will fail,

but the costs will be small and will fall on those willing

to bear them – entrepreneurs and their investors. Most

important, a few of the ideas will succeed, enriching the lives

of both producers and consumers. The market economy in that

sense works like a giant supercomputer, but one that computes

correctly only when the government ensures that conditions

are favorable and supportive of financial, entrepreneurial,

and managerial enterprise.

George David Smith is clinical professor of economics and

international business, Richard Sylla is Henry Kaufman Professor

of the History of Financial Institutions and Markets and professor

of economics, and Robert Wright is clinical associate professor

of economics at NYU Stern.

![]()