n the recent wave of corporate scandals,

from Enron to Tyco, poor corporate governance structures have

clearly been a contributing

factor. The tales of excess compensation, poor capital allocation,

and, occasionally, outright theft, have shone a harsh spotlight

on the relationships between chief executive officers and the

boards of directors. Too frequently, directors – who are

supposed to represent the shareholders – have acted in

ways that enrich CEOs and other favored executives while impoverishing

common shareholders. n the recent wave of corporate scandals,

from Enron to Tyco, poor corporate governance structures have

clearly been a contributing

factor. The tales of excess compensation, poor capital allocation,

and, occasionally, outright theft, have shone a harsh spotlight

on the relationships between chief executive officers and the

boards of directors. Too frequently, directors – who are

supposed to represent the shareholders – have acted in

ways that enrich CEOs and other favored executives while impoverishing

common shareholders. On many boards, two (or more) directors

serve together on a different company’s board. For example, General Motors Corp.’s

April 2002 proxy revealed that the GM board had two mutual interlocks:

CEO John F. Smith, Jr., and Director George M.C. Fisher were

also directors on the board of Delta Air Lines, Inc.; and Smith

and Director Alan G. Lafley were also on the board of the Proctor & Gamble

Co. (where Lafley is the CEO). We dub these associations “mutual

interlocks.” And in a sample of 366 large companies, 87

percent had at least one mutual interlock in 1991.

Director

interlocks have clear consequences for shareholders. Our

empirical analyses show that CEO compensation

tends to increase

and CEO turnover tends to decrease when the CEO’s board

has one or more pairs of board members who are mutually interlocked

with another company’s board. Why? On the one hand, mutual

interlocks could be an indication of and a contributor to CEO

entrenchment, from which higher compensation and lower turnover

naturally follow. On the other hand, mutual interlocks may indicate

the strengthening of important and valuable strategic alliances.

And the higher CEO compensation and lower turnover may be a just

reward for orchestrating such alliances. We believe that the

first interpretation is more accurate.

Director Interlocks

Researchers from several disciplines have been looking into interlocks

for several decades. And at first it appeared that interlocks

were a sign of weakness. In one of the earliest such U.S. studies,

economist Peter Dooley in 1969 found that less-solvent firms

were likely to be director-interlocked with banks. Later studies

also reported that firms with high debt-to-equity ratios, or

that had an increased demand for capital were likely to have

interlocks. The reason: Financially stressed firms may seek to

add bank officers to their boards to receive more favorable consideration.

Or banks may demand board seats so they can monitor firms more

closely.

Organizational behavior experts have

examined the extent to which a board is an instrument of

management interests. Some have argued

that companies use board interlocks as a mechanism to improve

contracting relationships, or to reduce the information uncertainties

created by resource dependencies between firms. This stream of

research suggests that the composition of boards, including interlocks,

is largely determined by the efforts of CEOs to influence the

selection of new directors so that they are responsive to that

particular CEO’s interests.

Financial economists have examined interlocks

as well. Kevin Hallock of the University of Illinois found

that CEOs serving

in employee-interlocked firms earn higher salaries than they

otherwise would. Nevertheless, existing research has not documented

a connection between director interlocks and total CEO compensation.

And in our survey of previous studies, we did not find any associations

between interlocks of various kinds and firm performance. That

leads us to believe that interlocks aren’t designed to

serve a firm’s strategic goals, and don’t serve them

in practice.

Compensation and Turnover

Several recent studies have examined the relation between top

executive compensation and board composition. And they report

mixed results. For example, some authors have found a positive

association between CEO compensation and the percentage of outside

directors on the board. Other studies have found no relation

between a board majority of outside directors and top management

compensation. The level of incentive-based executive compensation

appears to be positively connected with firm performance, and

incentive-based compensation appears to be used more extensively

by outsider-dominated boards.

“After

poor firm performance, CEOs are more likely to be dismissed

if the board of directors has a majority of outsiders.”

|

Other

scholars have found an inverse relation between the probability

of a top management change

and prior stock price performance.

After poor firm performance, CEOs are more likely to be dismissed

if the board of directors has a majority of outsiders. Empirical

analyses indicate that the probability of top management turnover

is reduced if the top executives are members of the founding

family or if they own higher levels of stock. Executive turnover

is also negatively related to the ownership stake of officers

and directors in the firm and positively related to the presence

of an outside blockholder. Other studies have found that the

likelihood of CEO departure is inversely associated with both

the dollar value of stock option compensation in relation to

cash pay and the amount by which a CEO’s compensation is

higher than would be expected from comparisons with the compensation

of other CEOs. But thus far, no study has considered the possible

effects that boards with mutual director interlocks have on CEOs’ total

compensation and turnover.

The Data

We looked at CEO compensation and CEO

turnover for 452 industrial firms, first compiled by NYU

Stern professor David Yermack. These

firms were drawn from Forbes magazine’s lists of the largest

500 U.S. companies in categories such as total assets, market

capitalization, sales, or net income. The data set includes all

companies meeting this criterion at least four times during the

1984-1991 period. Compensation data were collected from the corporation’s

SEC filings. Directors who were full-time company employees were

designated as “inside” directors. Individuals closely

associated with the firm – for example, relatives of corporate

officers, or former employees, lawyers, or consultants, or people

with substantial business relationships with the company – were

designated as “gray” directors. All the rest were

designated “outside” directors. We also drew on the

data assembled by Kevin Hallock, who analyzed 9,804 director

seats held by 7,519 individuals in 1992. We took as our final

data set the 366 industrial firms for the 1991 proxy season that

appeared in both the Yermack and the Hallock data sets. (Utility

and financial firms were excluded from the study because government

regulation may lead to a different role for directors.)

In order to examine how director interlocks

may affect CEO compensation, we used a measure of total remuneration

that included salary

and bonus, other compensation, and the value of option awards

when granted. We believe that this sum is a more accurate measure

of what boards intended to pay, which could be different from

what CEOs earn, since CEOs often exercise options early, thereby

sacrificing a significant portion of the award’s value.

As an estimate for CEO turnover, we

used a dependent variable that was set equal to one if a

CEO leaves office during the last

six months of the current fiscal year or the first six months

of the subsequent period. In order to control for retirement-related

voluntary departures, we included in the analysis the CEO’s

age. Turnover events occurred in 9.0 percent of the sample (thirty-three

firms).

Considering Interlocks

The key explanatory variable of this

study was the number of mutual interlocks on the firm’s

board. While two boards can be interlocked if they share

one director, they are mutually

interlocked if they share at least two directors. For any given

board, a director could be part of more than one pair of mutual

interlocks, so it is quite possible that a board may have a greater

number of mutual interlocks than directors. In our sample of

industrial firms, board sizes ranged from four to 26, with an

average of 12.18. The number of mutual interlocks ranged from

zero to 42, with an average of 12.15. The key explanatory variable of this

study was the number of mutual interlocks on the firm’s

board. While two boards can be interlocked if they share

one director, they are mutually

interlocked if they share at least two directors. For any given

board, a director could be part of more than one pair of mutual

interlocks, so it is quite possible that a board may have a greater

number of mutual interlocks than directors. In our sample of

industrial firms, board sizes ranged from four to 26, with an

average of 12.18. The number of mutual interlocks ranged from

zero to 42, with an average of 12.15.

Other independent variables used in

the study were based on their likely relevance and effects

on CEO compensation and CEO turnover,

as established by other authors. As in numerous other studies,

Tobin’s Q (the market value of assets divided by the replacement

cost of assets) was used as a proxy for the growth opportunities

of the firm.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of the key variables

in this study and their correlation with the number of board

director interlocks. As seen, the mean number of directors who

are CEOs of other firms is 1.94. This result is similar to that

reported by James Booth and Daniel Deli, who found the mean to

be 1.87 for 1989-90 data. The mean number of outside directors

serving on the board was 6.94, which is also consistent with

the previous literature.

Two Hypotheses

If the CEO dominates the selection process of directors to the

board, and if the CEO is in fact filling the director positions

with sympathetic members, then we would expect a positive association

between the fraction of these favorable board members and the

compensation of the CEO. In other words, our first hypothesis

stipulates that boards with a larger number of mutual director

interlocks will pay a higher compensation package to the CEO.

Our second hypothesis states that there is an inverse association

between the presence of mutual interlocks and the likelihood

of CEO departure.

What do the results show? The correlations reported in Table

1 suggest the existence of a relationship between the number

of mutual director interlocks and the compensation of the CEO.

It is not surprising that larger boards have more interlocks

and that a preponderance of interlocks appears to be positively

connected with outside directors and with directors who are CEOs

of other organizations. Mutual director interlocks appear to

be curtailed by close ownership and governance structures. Our

results show a negative and significant correlation between this

variable and the indicators for CEO-as-founder and for non-CEO

chairman.

Since director interlocks could just be indicators of strategic

power relationships between firms at the highest level, it cannot

be automatically concluded that CEOs and interlocked directors

exploit networks of board memberships for their personal gain

simply because these multiple board affiliations exist. In fact,

CEOs could be rewarded with additional compensation and long

job durations for successfully establishing mutual interlocks

that serve the strategic goals of the firm.

But the data show a significant negative

relationship between the number of mutual interlocks and

the number of “gray” directors,

many of whom could represent companies that have supplier or

customer relationships with the company. This negative relationship

reinforces our skepticism as to the likelihood that the mutual

interlocks serve the strategic goals of the firm.

Extra Compensation

To test our first hypothesis, we ran

an ordinary least square regression to estimate the effect

that mutually interlocking

boards have on the total compensation of the CEO. These calculations

took into account factors such as interlocks, firm size, tenure

of the CEO, firm performance, and stock ownership of the CEO.

The results of this estimation are presented in Table

2. As expected,

the number of mutual director interlocks is found to be significant

and positively associated with total compensation. This finding

suggests that the links created by the mutual interlocking relations

between boards actively benefit the CEO. In other words, with

the aid of mutual interlocks, CEOs are able to extract significantly

larger compensation packages from their firms. The robustness

of this result is upheld through further investigations of the

components of the CEO’s pay package. To test our first hypothesis, we ran

an ordinary least square regression to estimate the effect

that mutually interlocking

boards have on the total compensation of the CEO. These calculations

took into account factors such as interlocks, firm size, tenure

of the CEO, firm performance, and stock ownership of the CEO.

The results of this estimation are presented in Table

2. As expected,

the number of mutual director interlocks is found to be significant

and positively associated with total compensation. This finding

suggests that the links created by the mutual interlocking relations

between boards actively benefit the CEO. In other words, with

the aid of mutual interlocks, CEOs are able to extract significantly

larger compensation packages from their firms. The robustness

of this result is upheld through further investigations of the

components of the CEO’s pay package.

When we repeated the analysis using

the natural log of only the sum of the CEO’s salary and bonus as the dependent variable,

the coefficient for mutual directors was positive and significant.

That suggests that even just the sum of the CEO’s basic

salary and bonus tends to increase as a consequence of the mutual

director interlocks. In fact, we found that a mutual interlock

adds an average of $143,000 (approximately 13 percent) to the

average CEO salary and bonus.

The evidence presented in Table

2 is

in line with the view that mutual interlocks may indeed assist

the CEO in extracting lucrative

remuneration packages from the firm. The networks and traffic

of influences created by mutual interlocking directorships have

probably been utilized by CEOs in exerting control over the majority

of board members. This finding suggests that directors may not

be making decisions that benefit the firm’s shareholders

the most. Mutually interlocking directorships could be weakening

the control mechanisms put in place to ensure that directors

fulfill their fiduciary duty and act in the best interest of

the shareholders.

When we ran other regressions with these

data we found that stock option compensation appears not

to be judiciously used by boards

in compensating their CEOs in the presence of mutual interlocks.

We believe this reflects cronyism and weakens the board’s

monitoring function. This interpretation is consistent with the

view of academics and corporate governance activists who perceive

interlocks generally as corrupt. Thus, although other studies

find that markets react favorably to the adoption of stock option

plans to compensate top executives, we find that stock options

can be misused if the board’s monitoring activities are

weakened by interlocks.

Other results in these regressions are

consistent with the previous literature. We found that CEO

pay is inversely related to the

fraction of equity held by the CEO. And as economists Sherwin

Rosen, Clifford W. Smith, Jr., and Ross L. Watts have found in

other studies, we find that large companies and firms with greater

growth opportunities pay more to their CEOs. A company’s

net-of-market stock return was found to have a positive and significant

association with total CEO compensation, consistent with previous

studies.

CEO Turnover

To test our second hypothesis, we investigated

whether the presence of mutual interlocking directorships

decreases the board’s

ability to monitor the CEO, thereby decreasing the likelihood

that the CEO will depart. We analyzed the data, including CEO

and company characteristics that should be associated with the

probability of turnover. Michael Jensen and Kevin Murphy have

suggested that one obvious CEO feature likely to affect the turnover

process is age. To control for this influence we included the

CEO’s age in the estimation. And to control for firm performance,

we included the firm’s current and previous year stock

returns net-of-market as well as the current period return on

assets. Further control variables included proxies for growth

opportunities (the ratio of research and development {R&D}

over sales), the ratio of long-term debt to total assets, company

size, and the fraction of common stock held by the CEO or his

immediate family.

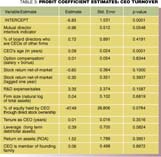

Table 3 presents coefficient estimates for the CEO turnover model.

And the results are as hypothesized: The coefficient on the mutual

interlock variable is negative and significant as predicted,

implying that the presence of mutual board interlocks is inversely

associated with the probability of CEO turnover. We interpret

this result to indicate that mutually interlocking directorships

weaken the monitoring power that the board has over the chief

executive. Further, mutual interlocks contribute to the possible

entrenchment objectives of the CEO. This result is in agreement

with the notion that boards are ineffective in controlling the

CEO, who is likely to control the nomination and selection process

of the directors.

These results are consistent with other theories and research

on CEO turnover. As previous studies have noted, we found that

CEOs are less likely to leave office if they own a large fraction

of equity in the firm or if company performance is strong. And

we found that age is positively associated with the probability

of CEO turnover. Firm size, as proxied by the natural log of

the firm assets, does not appear to play a role in the likelihood

that the CEO leaves office.

Conclusion

Academics and the popular press have suggested that corporate

boards are ineffective in monitoring CEOs, since CEOs frequently

dominate the director selection process. Boards filled with CEO-sympathetic

director appointees are likely to overcompensate and undermonitor

the chief executive. Our view is that the mutually interlocking

directorships that are prevalent among firms are responsible

for the production of sympathetic directors. These directors

have the opportunity to pay and re-pay each other favors because

of their multiple board memberships and may well be doing so

in league with the CEOs who nominated them.

“Interlocking

directorships weaken the monitoring power that the board

has over the chief executive.”

|

Our results

indicate that the power alliances created by directors with

multiple memberships

are used by self-serving CEOs to extract

handsome remuneration packages from firms and to strengthen their

entrenchment. Boards that overcompensate and undermonitor the

CEO are not fulfilling their fiduciary duties to the shareholders.

As a result, board mutual interlocks weaken the firm’s

governance structure, promote cronyism, and exacerbate the firm’s

agency problems.

The results reported here indicate that it is at least plausible

that mutual director interlocking relationships between different

corporate boards might affect the voting patterns and decisions

that these boards make on other matters besides CEO compensation

and turnover.

Overall, our research suggests that

inter-board relationships should be more closely scrutinized

to determine whether these

relationships encourage decisions that enhance shareholder wealth

or instead facilitate empire building by self-serving CEOs. If,

as we suspect, the latter is the case, then closer monitoring – private

and/or public – of boards is needed.

Eliezer M. Fich, Stern Ph.D. 2000, is visiting assistant professor

of finance at the Kenan-Flager Business School at the University

of North Carolina. Lawrence J. White is Arthur E. Imperatore

professor of economics at NYU Stern.

This article is adapted from an article that appeared in the

Fall 2003 Wake Forest Law Review. |

![]()