early

40 years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, residential

and commercial segregation remain a fact

of life in America.

Due to prevailing institutional, residential and social segregation,

demographic groups that are generally in the minority – African-Americans,

Asian-Americans, Hispanics and immigrants – predominate

within urban central cities. And yet in many of those same areas,

a majority of business owners are white. early

40 years after the passage of the Civil Rights Act, residential

and commercial segregation remain a fact

of life in America.

Due to prevailing institutional, residential and social segregation,

demographic groups that are generally in the minority – African-Americans,

Asian-Americans, Hispanics and immigrants – predominate

within urban central cities. And yet in many of those same areas,

a majority of business owners are white.

White entrepreneurs in central cities face the novel experience

of working in a social context in which they are racial minorities,

while at the same time they are a part of the dominant coalition

of firm owners and are members of the majority within the larger

society.

Entrepreneurs in urban contexts find that they must build relationships

across racial and ethnic boundaries. But “tokens” – numerical

minorities in organizations or contexts dominated by the majority – face

considerable challenges in doing so. That’s because cross-race

relationships, within and outside of organizations, remain relatively

unusual. In his 1987 study of core discussion networks, Harvard

sociologist Peter Marsden found that only eight percent of Americans

reported any racial or ethnic diversity in their networks, with

white Americans having the greatest homogeneity.

In the inner-city context, then, those with the least experience

in forging cross-racial relationships have the greatest need

to do so. White entrepreneurs in central cities usually cannot

leverage their personal knowledge of co-ethnic customer tastes

and appeal to bounded solidarity to build protected markets.

While these firm owners may choose to focus on building cross-race,

central city relationships personally, they may also establish

relationships with other institutions or individuals – “social

brokers” – that can provide links to immigrant and

ethnic groups. Government agencies, non-profit and service organizations,

religious institutions, and even current customers or employees

can serve as social brokers, yet not be explicitly dedicated

to this practice. We set out to determine the role and significance

of social brokers in helping white entrepreneurs in central-city

locations forge cross-racial and cross-ethnic links with employees

and customers.

Then and Now

In his classic 1973 study of discrimination in hiring, sociologist

Howard Aldrich examined patterns of firm ownership in the predominantly

black neighborhoods of Roxbury (Boston), Fillmore (Chicago) and

Northern Washington, DC. The majority of the employers (55 percent)

in these areas were white, and whites were minorities in the

residential population (ranging from 10 percent of the population

in Fillmore to 28 percent in Roxbury). Aldrich also found that

80 percent of the white firm owners were “absentee owners.” White

firm owners were more likely to hire people who lived outside

of the neighborhood and were more likely to hire white employees

than non-white central city firm owners. Other studies at the

time found similar ownership patterns in other cities.

Do these conditions still persist? In 1970, when Aldrich’s

data was collected, each of the neighborhoods studied had only

a decade earlier been predominantly white. Aldrich tied the pattern

of white firm ownership to an inability of white firm owners

to leave as rapidly as white residents.

But the “white flight” context of the early 1970’s

no longer exists in central cities. White residents have long

been gone from these neighborhoods, and the absolute number of

businesses has declined significantly. So today’s central

city firm owners are more likely to be located there by choice.

A second difference is the considerable influx of non-white immigrants

from Asia, Central America and the Caribbean. Previous studies

have shown these groups to have high incidence of entrepreneurship.

To update Aldrich’s study, we analyzed a subsection of

employer respondents from the Multi-City Study of Urban Inequality

(MCSUI). This data was collected by researchers in Atlanta, Boston,

Detroit and Los Angeles between 1992 and 1995 to examine labor

market dynamics, with a particular focus on jobs requiring no

more than a high school education. Table

1 presents the incidence

of white firm ownership by metropolitan area subsection, based

on 510 respondents.

As found in studies from the 1970s, the dominant coalition of

firm owners are white (84.9 percent), and seven of every 10 firm

owners in predominantly non-white central city areas are white.

The percentage of white firm ownership in central city areas

is even greater than in studies from the early 1970’s.

Why? It has long been argued that whites have greater access

to critical capital stocks, making them better able to start

firms and to weather economic hardships than their black and

Hispanic counterparts. Second, black central city neighborhoods

have been especially hard hit by the exit of the middle class,

who had options to move after segregation declined in the 1970’s.

We then analyzed responses of firm owners regarding the incidence

of white customers and employees by city subsection. In central

city areas, where the majority of the residents are non-white,

the white/nonwhite composition of the customer base and employee

base is evenly split (50.1 and 47.5 percent, respectively). However,

there is considerable variation across firms in terms of their

customer and employee demography. The standard deviation was

35.1 percent for white customers, and 40.5 percent for white

employees.

Hiring Patterns

Next, we set out to determine the influence of owner race on

racial composition of the employment base. Because Aldrich found

that differences in firm type (e.g., retail, service or manufacturing)

accounted for some of the differences in hiring patterns, we

controlled for sector of employment in our analysis.

In line with the findings of studies from a generation ago, we

found that the race of the firm owner influences hiring patterns,

even when adjusted for firm location and industrial sector. White

firm ownership increased the percentage of white employees by

an average of 40 percent.

Aldrich generated four hypotheses regarding the possible role

of discrimination in hiring patterns. First, white employers

may simply prefer associating with whites over blacks. Second,

white employers might practice statistical discrimination, in

which negative beliefs about the work fitness of blacks cause

employers to prefer not to hire black employees. Third, white

employers might avoid hiring blacks because of negative reactions

of other employees or the firm’s customers. Fourth, white

employees might be over-represented because whites who worked

in the firms prior to the wholesale white exodus from the neighborhood

hung on to their jobs in these neighborhoods. Aldrich was ultimately

unable to determine whether discrimination accounted for the

overrepresentation of white employees in white-owned firms located

in black neighborhoods.

Today, two of these hypotheses are less useful. The customers

of firms in today’s central city areas are as likely to

be white as non-white. And because white flight is no longer

a recent phenomenon – as it was in the 1970s – there

is a low potential that the current set of white employees were

unable to find work elsewhere. The second hypothesis, that white

employers have developed a “distaste” for non-white

labor, has been examined by other researchers. In interviews

with white employers in central city areas, employers expressed

their tendency to practice statistical discrimination with black

applicants because of past experiences with negative workplace

attitudes and behaviors. Sociologist William Julius Wilson in

1996 examined black employers from the same neighborhood, and

found that they expressed similar views of the attitudes and

work ethic of central city black employees.

But employer distaste probably doesn’t explain the differences

in hiring patterns by race of owner observed above. Perhaps white

employers, like other tokens, face barriers in establishing cross-race

relationships that might assist them in locating the most qualified

employees from the local pool of labor. Given the generally low

opinion employers appear to have of central city labor, reference-based

hiring may be one of the prime means of ensuring labor quality.

Weak Ties

In his classic 1973 study of personal contacts in job-seeking,

sociologist Mark Granovetter found that the overwhelming majority

(83 percent) of managerial and professional job seekers found

their jobs through acquaintances with whom they spoke occasionally

or rarely. This finding of the “strength of weak ties” is

one of the more influential ideas in the social sciences.

But Granovetter’s reanalysis of Stanley Milgram’s

data on interracial acquaintance chains has been less discussed.

Granovetter reanalyzed the success rate of white senders who

attempted to deliver a booklet to black targets through acquaintance

chains, if the first connection between a white sender and a

black recipient described the black person as a “friend” or

an “acquaintance.” Granovetter found that the weak

tie instances – those where the first black connection

was described as an acquaintance – were twice as likely

to result in a successful completion to the eventual target.

Weak acquaintance ties were more successful than strong friendship

ties in reaching cross-race targets.

Given this, we hypothesize that cross-race weak ties might also

assist in the recruitment of employees. And institutions or individuals

that bridge socially segregated groups are a form of weak tie

relationship that employers can use to mediate their token status.

Connections through community service organizations, religious

institutions, civic leaders, and current employees might assist

employers in locating qualified minority employees and result

in larger numbers of minority employees.

Using Social Brokers

Hiring proper employees is a critically important task for a

firm owner. But when the employer is white and the employees

are generally non-white, the hiring challenge may be especially

difficult. A racial “outsider” may find it tough

to accurately screen an applicant during the hiring process and

reveal potential behavioral or attitudinal mis-hires. Once employees

are hired, white employers may worry that negative on-the-job

feedback will result in accusations of racial prejudice. Given

the distrust, doubt and accusations that can sometimes accompany

cross-race interactions in central cities, some entrepreneurs

may choose to avoid central city locations or minority employees

altogether.

The MCSUI contained a series of questions regarding the methods

used by employers in hiring for their last employment vacancy.

The positions were those that did not require the applicant to

hold a college degree. We investigated the influence of hiring

methods that involved social brokers on minority hiring rates

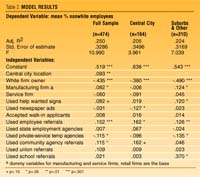

in central cities. Table 2 presents the results of three linear

regression analyses using dummy variables to determine the influence

of the race of owner, city subsector, industry sector and hiring

methods on the percentage of non-white employees in the firm. The MCSUI contained a series of questions regarding the methods

used by employers in hiring for their last employment vacancy.

The positions were those that did not require the applicant to

hold a college degree. We investigated the influence of hiring

methods that involved social brokers on minority hiring rates

in central cities. Table 2 presents the results of three linear

regression analyses using dummy variables to determine the influence

of the race of owner, city subsector, industry sector and hiring

methods on the percentage of non-white employees in the firm.

The analysis of the full set of firms shows that manufacturing

firms are more likely to hire non-white employees. This is likely

due to the greater need for unskilled labor in these firms. The

first evidence of social brokerage is found in the strong influence

of employee recommendations on the percentage of non-white employees.

Both the magnitude of this coefficient and its high level of

significance is persuasive evidence of the use of this practice

among entrepreneurs. The use of help wanted signs was also shown

to increase the percentage of non-white employees. Help wanted

signs are a strategy for employers seeking to attract employees

that happen to pass the firm location, and may be a means to

hire from the local community without aid of brokerage.

Private-service temporary agencies appear to serve as brokers

for firms seeking to hire white employees, while community agencies

serve firms seeking non-white employees. These differences are

likely generated by the divergent customer needs that each agency

serves.

Even after controlling for city subsection, industry and hiring

method, the strongest influence on percentage of non-white employees

is still the race of firm owner. This suggests that our analysis

has failed to account for other factors influencing the hiring

choices of white owners, and that these results do not rule out

preferences for homophily.

Help Wanted

Splitting the files by city subsection allowed us to compare

the incidence of brokerage strategies by firm location. We found

that outside central city areas, manufacturing firms have a greater

tendency to hire non-white employees, and help wanted signs increase

the percentage of non-white employees. An alternative perspective

is that employers located in suburban areas are familiar with

available local labor (predominantly white), and use help wanted

signs as an “affirmative action” strategy, designed

to attract potential employees that are not in their current

social network.

Employers may find that non-white applicants that learn of their

openings by passing their location are more likely to be “acculturated” or

familiar with the workplace behaviors necessary to work in suburban

contexts. The positive finding for all firms appears to be driven

by the use of this brokerage strategy in central cities. Outside

of central cities, employers utilize current employees as brokers

for non-white employees, though to a lesser degree. Private-service

temporary agencies play a strong role in bringing white employees

into firms. Finally, referrals from educational institutions

enhance non-white hiring outside central cities. It appears that

for firm owners in these areas, educational institutions play

a brokerage role in assisting in the hire of non-white employees.

Customer Relations

Entrepreneurs must also manage another critical constituent group

on the demand-side of the equation: customers. Customers are

not only a firm’s source of revenue, they are a prime means

of attracting new customers through word-of-mouth. But for white

entrepreneurs operating in central city areas, building relationships

with customers from the local community may present many of the

same challenges found in locating employees. White firm owners

are less likely to be personally familiar with community members

and are less likely to be personally aware of emerging customer

tastes and needs. Non-white customers may resent the presence

of white firm owners, and customer dissatisfactions may take

on an accusatory tone generally not experienced in contexts where

the customers are predominantly white. There is a historical

legacy of mistreatment of minority customers in businesses owned

by white proprietors. White central city entrepreneurs may therefore

attempt to use employees as brokers to manage potentially fractious

relations with a substantial base of non-white customers.

We set out to determine the influence of customer demography

on the makeup of a firm’s labor pool. If increasing percentages

of non-white customers positively influences the percentage of

non-white employees, it would suggest that employers use employees

as social brokers to manage relationships with customers. To

investigate, we ran a linear regression analysis of race of firm

owner, industry sector, firm location, and percentage of non-white

customers on the mean percentage of non-white employees.

The results of this analysis are consistent with the hypothesis

that customer demography explains some of the variance in employee

demography even after controlling for race of firm owner. Subsequent

analyses of these influences by firm location showed the same

pattern of results throughout. However, the magnitude changes

of coefficients provided some interesting findings. First, when

compared with the prior analysis of employer race influence on

employee demography, the coefficient for white firm owners decreased

when the predictor variable for customer demography was entered.

Some of the variance explained by employer race in the earlier

analysis is now shown to result from customer demography. Second,

white customers have a positive influence on the number of white

employees in all locations, although the relationship became

stronger in suburban areas. Third, white firm owners have an

even greater positive influence on the percentage of white employees

in central city areas. This suggests one of two alternative hypotheses:

a) white firm owners in central city locations have an even greater

preference for white employees than in suburban areas; b) white

firm owners face even greater challenges in locating non-white

labor in central city areas. Given our theoretical framing of

white firm owners as tokens we suspect the latter.

Emerging Markets

Taken together, our findings suggest that relationships play

a critical role in job seeking, especially when operating cross-racially.

And understanding this dynamic is becoming more important. For

over the past several decades, patterns of social and racial

segregation have created structural holes, which in turn have

created economic opportunities in central cities – America’s

emerging domestic markets.

Entrepreneurs of all races and ethnicities are figuring out how

to build wealth while providing jobs and leadership that diminish

many of the social problems we’ve come to associate with

inner city communities. In May 2003, Inc. magazine released its

annual list of the most rapidly growing inner-city firms. The

characteristics of the members of the Inner City 100 may seem

surprising: average sales of over $25 million, and five-year

growth rates over 600 percent.

Social brokers will play an important role in developing these

markets further. America’s inner- city neighborhoods will

increasingly show promise as sites for investment, and many of

the entrepreneurs pursuing these opportunities will not be ethnic

and racial minorities. On Inc.’s list, 62 percent of the

firm owners were white. Locating high quality employees in a

cross race situation requires the recognition that relationships

matter and that relationships tend to stay within the same race.

Without building social brokerage relationships, employers run

the risk of missing the most qualified members of the labor pool.

Gregory B. Fairchild is assistant professor of management at

Darden Graduate School of Business Administration at the University

of Virginia

Jeffrey A. Robinson is assistant professor of management at NYU

Stern. |

![]()