|

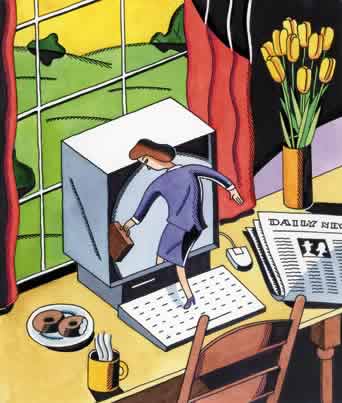

The advent

of portable computing and the Internet has rapidly opened up possibilities

for a new mode of work: teleworking. This new workstyle is more

flexible and dynamic than telecommuting, which has typically simply

meant working from home. Under telework, employees are based wherever

their work happens to be.  But

the growth of telework is a double-edged sword. The upside? Employees

are able to work from their cars, hotels, or airplanes, and out

of other firm’s offices, and from their homes, and on weekends

and at night. The downside? Employees may be expected to work

from their cars, hotels, or airplanes, and out of other firm’s

offices, and from their homes, and on weekends and at nights. But

the growth of telework is a double-edged sword. The upside? Employees

are able to work from their cars, hotels, or airplanes, and out

of other firm’s offices, and from their homes, and on weekends

and at night. The downside? Employees may be expected to work

from their cars, hotels, or airplanes, and out of other firm’s

offices, and from their homes, and on weekends and at nights.

Telework

presents challenges to both management and workers, and their

relations with one another. After all, most corporate work cultures

are designed to support face-to-face work activities at the office.

And while some employees find the teleworking notion natural and

attractive, others find the idea of working continually untethered

and off-site disconcerting. Telework

presents challenges to both management and workers, and their

relations with one another. After all, most corporate work cultures

are designed to support face-to-face work activities at the office.

And while some employees find the teleworking notion natural and

attractive, others find the idea of working continually untethered

and off-site disconcerting. Under

the right circumstances, of course, telework can lead to that

great desideratum: improved quality of life. And yet some employees

will fret about the meaning of corporate membership if they have

no physical corporate office they can call their own. Telework

also terrifies some managers. After all, how do you motivate and

supervise employees you rarely see? Under

the right circumstances, of course, telework can lead to that

great desideratum: improved quality of life. And yet some employees

will fret about the meaning of corporate membership if they have

no physical corporate office they can call their own. Telework

also terrifies some managers. After all, how do you motivate and

supervise employees you rarely see?

anaging in the

culture of telework requires executives and workers alike to cast

off long-held beliefs and adopt new ones. For telework, by its

nature, transforms the way a company lives and breathes. It alters

the very genetic make-up of an organization. Rather than being

stable and revolving around the workplace, telework is highly

dynamic and centers around the work people do. anaging in the

culture of telework requires executives and workers alike to cast

off long-held beliefs and adopt new ones. For telework, by its

nature, transforms the way a company lives and breathes. It alters

the very genetic make-up of an organization. Rather than being

stable and revolving around the workplace, telework is highly

dynamic and centers around the work people do.

Wrenching a company around to accommodate telework is a process

– more like turning around a battleship than clicking a mouse.

It takes time. And throughout history, changes in corporate culture

have rarely come easily or without pain.

Back in the 1760s, Josiah Wedgwood tried to bring the techniques

of mass production to his pottery factory. But the local laborers,

accustomed to working at their own rhythms, chafed at the new

behavioral constraints. Mr. Wedgwood’s response would have

made Chainsaw Al Dunlap proud. He imposed stiff fines for transgressions

and created a supervisory career structure that rewarded those

who followed the rules with easier work and higher pay. Eventually,

Mr. Wedgwood attracted a work force willing to play by his rules.

The new work culture was epitomized by the idea: “You are

paid to do, not to think.”

Such managerial impositions curtailed human creativity. But they

also harnessed machine productivity and forged a new industrial

culture in the 19th century. Encouraged by productivity gains,

the architects of industrialization continued to explore how a

work logic based on ever more refined divisions of labor could

further increase productivity. Eventually, much mass production

work became completely meaningless to the workers and many viewed

it as exploitative.

The mass-production culture bore fruit: think Henry Ford’s

Model T. But it also wrought strikes, violence, and sabotage.

The crisis it imposed ultimately shifted power from management

to labor unions, and required managers to reconsider the meaning

of work. In response, a new management culture slowly emerged

based on the notion that more meaningful work experiences would

improve work performance. This led to recommendations that increased

worker participation and to extensive redesign of factories and

offices.

The advent of information technologies in the late 20th century

has set the stage for the next round of cultural change. In the

past, managers and entrepreneurs sought to boost efficiency by

manipulating structural designs – devising a better assembly

line or installing air-conditioning. But telework technologies

extend the human mind – they liberate rather than limit or

constrain thoughts and ideas. As a result, the great workplace

slogan of the 21st century may be: “You are paid both to

think and to do.”

omputers –

and the networks that link them – have changed the very locus

and mode of work. The Internet allows people to be in constant

contact with others who think in different ways. And as new information

becomes available, they may think about work matters differently.

Historically, the content of a work culture has been centered

on specific tasks. In the wired economy, however, participants

continually renegotiate and redefine the system of meaning –

the very nature of work. As a result, telework tends to evolve

and change quickly in unexpected ways. omputers –

and the networks that link them – have changed the very locus

and mode of work. The Internet allows people to be in constant

contact with others who think in different ways. And as new information

becomes available, they may think about work matters differently.

Historically, the content of a work culture has been centered

on specific tasks. In the wired economy, however, participants

continually renegotiate and redefine the system of meaning –

the very nature of work. As a result, telework tends to evolve

and change quickly in unexpected ways.

Indeed, telework makes it more difficult to identify and define

corporate cultures. Generally, organizations have relatively identifiable,

stable cultures. The members share norms, beliefs, and behaviors

that develop over time as a result of face-to-face interaction

and shared experiences. In many instances, managers lay down the

infrastructure of corporate culture.

When they introduce telework, managers must be aware of the way

it can affect corporate culture. If the organization portrays

the arrangements simply as a cost-reduction measure, the telecommuting

assignments may involve routine work. Technology may be used simply

to send and return assignments. Those who continue to work in

the office are likely to feel they have a preferred status while

those working outside are likely to feel they have been transformed

into a source of cheap, out-sourced labor. If teleworkers view

the firm’s actions as isolating, alienating, exploitative,

and devoid of human sensitivity, an unhealthy culture will develop.

In contrast, if the organization makes telecommuting assignments

with the intent of developing the firm’s human capital faster,

telecommuters may be seen to be among the privileged elite. And

as teleworkers anticipate and enjoy their relative independence

and flexibility, they may feel empowered and develop unique cultures

supportive of their work activities.

A teleworking company will differ, by its very nature, from a

traditional organization company. Organization culture is built

upon the ground of specified locations, determined tasks and bounded

social units. Members build a shared identity based on daily personal

contact. It is solid. You can see, touch, and feel it. As a result,

it is more likely to produce an enduring organizational identity.

The telework culture, by contrast, is built upon the ground of

individuals with computers working intensively on assigned tasks.

It’s more amorphous. The values, norms, behaviors, and symbols

that it forms around are associated with ongoing computer work

performance.

In a teleworking culture, employees interact differently with

one another. And that changes everything. Indeed, the use of e-mail

– simple as it may sound – becomes an enormously important

component of culture.

As any computer user knows, chatting by e-mail is far different

than talking in person. E-mail is far more dynamic than real conversation.

It requires high user involvement and interaction, but is also

easy to use. It takes little effort to turn on a computer and

send an e-mail – to one person or to forty – and there

is no need to be physically and temporally co-located with others.

Electronic and phone messages await teleworkers, which allows

teleworkers to be truly distributed over time and space.

Teleworkers tend to rely on e-mail to communicate with one another.

As a result, the overall emerging network content – the overarching

conversation among employees – reflects a combination of

individual user initiatives acting in conjunction with other interactions.

A person might send an e-mail that contains a link to a website,

or an attached file, or a photograph. A second person can pass

the message – or part of it – along to one person, or

to an entire group. In this way, the content of the conversation

is continually being influenced but never controlled by individual

teleworkers.

Teleworkers’ culture – their values, norms and beliefs

– are continually emerging through a constant process of

negotiation among the members of open and burgeoning e-mail networks.

Telework culture is thus composed of the partial and temporary

set of agreements members reach about a network’s current

values, norms, and beliefs. It offers a common ground to foster

interactions among the various team members involved in a particular

project. By using e-mail, groups of workers can easily add members.

This attribute generates an acceptance and expectation of fluid

memberships.

orous boundaries

are a corollary to fluid membership. Members can jump in and out

of chatrooms after they have made their contributions. And at

any point in time, teleworkers may in fact be members of several

groups. A chief financial officer may simultaneously be teleworking

with a company’s treasury staff on the budget and sitting

in on a branding strategy meeting. Consequently, teleworkers’

experiences from one work group impact processes in other groups.

The same individual may be running one task group and merely observing

another. Best practices gleaned from one group may be tried out

in another. And so the culture changes yet again. orous boundaries

are a corollary to fluid membership. Members can jump in and out

of chatrooms after they have made their contributions. And at

any point in time, teleworkers may in fact be members of several

groups. A chief financial officer may simultaneously be teleworking

with a company’s treasury staff on the budget and sitting

in on a branding strategy meeting. Consequently, teleworkers’

experiences from one work group impact processes in other groups.

The same individual may be running one task group and merely observing

another. Best practices gleaned from one group may be tried out

in another. And so the culture changes yet again.

E-mail also generates content in its very use. As teleworkers

exchange messages, information about their interactions and relationship

is recorded. And since these information threads are frequently

accessible, the e-mail record becomes a trace of evolving understandings,

with people applying their own perspectives and interpretations.

This mode of working can have its downsides. At some point, most

networks need to develop ways to summarize, simplify, and clarify

the understandings they have accumulated. This task becomes more

difficult in a telework culture. And as the numbers of people

involved in a conversation expands, the whole process can become

overwhelming: a Tower of E-Babel. Norms of interaction, designed

to maintain work focus and control, may overload. These norms

may include rules for how and when to respond to e-mails, the

topics that may be raised in a particular group, membership issues,

or the use of signals to communicate message urgency. They may

also include cultural understandings as to when to send an e-mail,

or when to phone. Or when a face-to-face meeting might be in order.

ven as norms

evolve, there is still no possibility that a stable cultural state

will emerge. Consider what happens when a new member is added

to an ongoing e-mail exchange network. The new member can get

up to speed by examining the records and asking questions of clarification

as needed. But once this happens, she will immediately begin to

add her own perspective and insight to the conversation. ven as norms

evolve, there is still no possibility that a stable cultural state

will emerge. Consider what happens when a new member is added

to an ongoing e-mail exchange network. The new member can get

up to speed by examining the records and asking questions of clarification

as needed. But once this happens, she will immediately begin to

add her own perspective and insight to the conversation.

How do collective values shape these fluid processes? In traditional

work groups, values – think quality, excellence, diversity

– are often considered to be stable. But the members of a

telework group are often not sure what is going to emerge from

their efforts. So they only evolve to an understanding of what

is not acceptable to the collective based on what is inviolate

at an individual level.

This issue is apparent in the way Hatim Tyabji, the CEO of Verifone,

Hewlett-Packard’s e-payment solutions unit, governed his

virtual enterprise. In defining his organization culture, Mr.

Tyabji suggested that Verifone would “create and lead the

transaction automation industry worldwide,” and his firm

would be close to customers and respond quickly to their needs.

To achieve these broad goals, Verifone mobilized many cross-functional

teams, many of which had members in different locations relying

on e-mail. While team tasks were defined, the methods by which

they would achieve those tasks were usually left undefined. Members

relied on each other’s ideas to determine what should be

done. Teams posted both progress and problems on corporate networks.

As situations arose, they sought help from across the company.

Members of Verifone who had worked at other corporations were

frequently astounded at the response speed created by these arrangements.

But the speed also generated tension and misunderstandings. And

it quickly became apparent that face-to-face interactions were

necessary to complement e-mail messages. As a result, one third

of Verifone’s employees were always on the road having “off-line”

meetings.

In traditional groups, individuals are likely to identify strongly

with specific group values. In telework groups, where employees

are likely to be members of more than one practice community at

the same time, employees can shift their identification from one

group to another depending upon the specific group that they are

operating in at any particular time. So instead of regarding themselves

as members of stable organizations, workers will see themselves

as affiliates of several constantly evolving entities.

In the past, executives and experts viewed culture as stable content.

But like evolution itself, telework culture is a process always

in-the-making. Every day, individuals with different interpretive

schemes show up for work – wherever that may be – and

negotiate the meanings associated with the information they exchange.

And that’s not the only tension created by the growth of

telework. In centered organizations, there is often widespread

agreement about the norms of interaction. But as organizations

grow more decentralized, interaction norms become subject to continuing

negotiation, and conflicts between member beliefs, organization

norms, and even its values may emerge.

Given such tensions, managers seeking to institute a new culture

may face the same type of resistance that Mr. Wedgwood did back

in the 1960s. But the modern-day process is likely to give rise

to new challenges. Instead of inviting the crisis of alienation

and meaninglessness that mass production brought, telework may

spawn boundarylessness and burnout. In our 24x7 world, after all,

distinctions between work and play inevitably blur. And that may

yet prove to be the Internet’s great contribution to commercial

culture.

Roger Dunbar is professor of management and organizational

behavior at Stern. Raghu Garud is associate professor of management

and organizational behavior at Stern.

|

![]()