|

By Ingo Walter

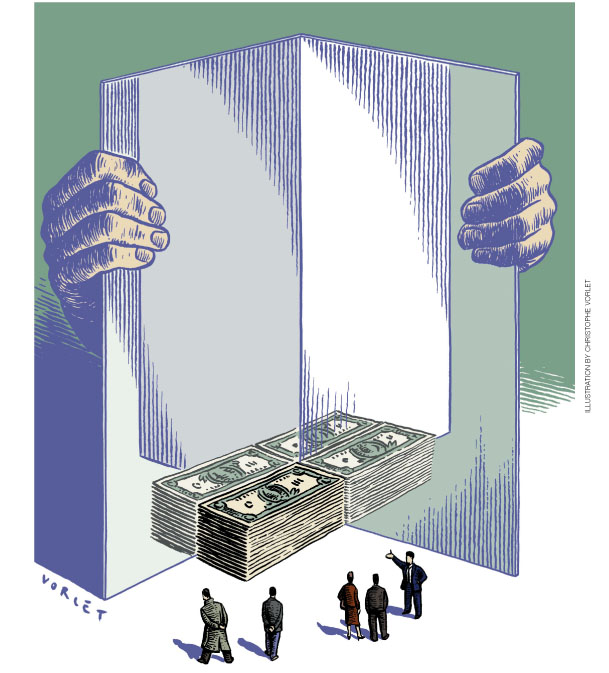

t must be magic. Take a small group of highly talented individuals, raise lots of risk capital from yield-hungry investment institutions and wealthy individuals who can tolerate possible losses, load-up on cheap debt to leverage investments, and opportunistically pursue control of an astounding array of new and established businesses around the world. If it works, everybody wins. Investors receive high, abnormal returns for the risk they take. Banks book loans at attractive spreads. And the owners and managers get seriously rich, with a few taking home over $1 billion in a good year. That’s the general idea behind private equity today. But what is the source of all these gains? And how sustainable is the business model? t must be magic. Take a small group of highly talented individuals, raise lots of risk capital from yield-hungry investment institutions and wealthy individuals who can tolerate possible losses, load-up on cheap debt to leverage investments, and opportunistically pursue control of an astounding array of new and established businesses around the world. If it works, everybody wins. Investors receive high, abnormal returns for the risk they take. Banks book loans at attractive spreads. And the owners and managers get seriously rich, with a few taking home over $1 billion in a good year. That’s the general idea behind private equity today. But what is the source of all these gains? And how sustainable is the business model?

The private equity business has been around for years in various guises, including LBO firms and “activist” hedge funds. Classic private equity firms are usually organized around a cluster of special-purpose limited partnerships run by their principals – people with outstanding financial skills, extensive business and political contacts, and substantial industry expertise. The principals invest as general partners in the funds they manage, alongside a limited number of qualified (wealthy) individuals and institutional investors who will share in any gains or losses – and, in the meantime, pay hefty management fees. In today’s environment of low interest rates and limited opportunities for high yields, many long-term investors are searching for total returns (“alpha”). For such investors, private equity is made to order.

With distinctive financial and industry expertise and investors locked-in for several years, private equity firms hunt for what they consider materially undervalued assets – mismanaged public companies, startups in promising industries, public-sector privatizations, corporate spin-offs, or corporations coming out of bankruptcy. The plan is to restructure the business and eventually exit with a substantial profit. For startups, that may mean long-term nurturing of the firm until it is ready to be sold to a trade buyer or to the public in an initial public offering. For established businesses, it usually means focusing intensively on improving cash-flows and reworking the financial structure to increase leverage – a task that isn’t too difficult given today’s global liquidity and cheap credit – as well as closing obsolete plants, streamlining production processes, improving products and services, unloading non-core businesses, and other related initiatives to make the business more valuable. Most (but not necessarily all) top management and the board will usually be replaced, and in the absence of scrutiny by the public markets, the private equity firm will single-mindedly dominate both management and governance processes using the best talent money can buy.

f all goes well, an exit will be found some time down the road that successfully monetizes the value of the enterprise and provides significant returns for the principals and their co-investors. Along the way, the principals will often pay themselves large consulting and management fees, sometimes financed by the debt the business takes on. These are profits that come on top of the expected capital appreciation. But, of course, things may not go as planned and expected returns on a particular investment may fail to materialize. In such instances, private equity investors hope to offset losses with more successful investments elsewhere in the fund’s portfolio. f all goes well, an exit will be found some time down the road that successfully monetizes the value of the enterprise and provides significant returns for the principals and their co-investors. Along the way, the principals will often pay themselves large consulting and management fees, sometimes financed by the debt the business takes on. These are profits that come on top of the expected capital appreciation. But, of course, things may not go as planned and expected returns on a particular investment may fail to materialize. In such instances, private equity investors hope to offset losses with more successful investments elsewhere in the fund’s portfolio.

Cleansing Agents

Private equity firms argue that they are the cleansing agents of the private enterprise system, and, as such, that they are doing well by doing good. They provide a critical source of equity capital for startups, streamline and restructure businesses that have underperformed, and give new life to industrial wrecks like Chrysler, where other owners have failed miserably. They replace obsolete corporate structures like conglomerates with clean, specialist companies able to leverage expertise and focus. They neutralize age-old conflicts of interest between managers and shareholders (the source of most corporate governance problems) by eliminating the distinction between the two roles. They galvanize public companies into self-improvement by their very presence and the knowledge that very few listed firms today are immune from private equity’s attentions, including club-deals that could go after the world’s largest companies. The collective angst induced by private equity firms makes private enterprise work better. And as they take companies private, they are able to shed some of the baggage that holds down public companies – short-termism, earnings guidance, analyst scrutiny, and share price volatility – and focus on realizing significant long-term values. In short, private equity represents an economic catalyst that can only improve capital formation, labor force allocation, productivity, and technology as an engine of growth for the general good.

"The benefits of private equity greatly exceed its costs. Private ownership traces its roots to the origins of capitalism and fuses risks, returns, control, and accountability in ways that are sometimes hard to duplicate in public markets." |

|

Critics concede some of these points, but argue that there are also important costs and risks to this process. Private equity firms have variously been called “asset strippers” and “locusts” in sometimes overheated debates. Private equity deals have become hot topics from Australia to South Africa, from continental Europe to Japan. Indeed, effective corporate restructuring often involves large-scale layoffs, the costs of which are borne by the individuals themselves or by society at large. Employees may be bludgeoned into concessions which leave ordinary people worse off even as the private equity investors accumulate outsize returns with effects on income distribution that could eventually undermine the political legitimacy of the market-based economy. Customers too may feel the heat as private equity owners take advantage of opportunities to exploit monopoly power and raise prices. And the financial engineering applied by private equity firms may increase bankruptcy risk and business survivorship under adverse conditions even as some of that debt is used to enrich private equity managers and reduce their exposure to possible failure – once again separating the interests of owners and managers.

In their defense, private equity firms argue that any job losses they impose are far fewer than the losses that would be suffered if the target companies failed, that destroying viable jobs makes no business sense, and that they have, on balance, created and not destroyed jobs. They promote the value of private equity in inhibiting key problems in public companies that have come to light, such as accounting scandals and earnings restatements, options backdating, management compensation unrelated to corporate performance, boardroom failures, and the like. And they argue that they comply with public policy constraints on corporate conduct, just like everyone else.

ho is right? No doubt there are good arguments on both sides. But I would argue that the benefits of private equity greatly exceed its costs. Private ownership traces its roots to the origins of capitalism and fuses risks, returns, control, and accountability in ways that are sometimes hard to duplicate in public markets. In any case, private equity usually depends directly or indirectly on public markets to provide an exit, so fears of serious impairment of those markets are overblown. On the other hand, private equity needs persistent inefficiency to thrive and, therefore, has its own dynamic of “creative destruction.” The more it succeeds, the narrower its market opportunities and the more it attracts competitors from the hedge fund sector, investment banks, financial conglomerates, and even principal-investment units of insurance companies and pension funds. Too much money may already be chasing increasingly marginal opportunities in the current financial cycle. ho is right? No doubt there are good arguments on both sides. But I would argue that the benefits of private equity greatly exceed its costs. Private ownership traces its roots to the origins of capitalism and fuses risks, returns, control, and accountability in ways that are sometimes hard to duplicate in public markets. In any case, private equity usually depends directly or indirectly on public markets to provide an exit, so fears of serious impairment of those markets are overblown. On the other hand, private equity needs persistent inefficiency to thrive and, therefore, has its own dynamic of “creative destruction.” The more it succeeds, the narrower its market opportunities and the more it attracts competitors from the hedge fund sector, investment banks, financial conglomerates, and even principal-investment units of insurance companies and pension funds. Too much money may already be chasing increasingly marginal opportunities in the current financial cycle.

"In the end, financial historians may find there was nothing 'magic' in the private equity boom after all. Rather, it may be that it was just a product of the times and the free market performing its function." |

|

Over $800 billion in private equity transactions have been completed worldwide since the beginning of 2005. Can it really be that the market-driven economy works so badly and that public companies are so badly managed that this volume of deals will end up being highly profitable for the private equity investors? Or that a single firm, Kohlberg, Kravis & Roberts (KKR), can account for 44.1 percent of global buyouts so far this year (including leading the $45 billion buyout of Texas energy producer TXU and the $20 billion buyout of UK drug store chain Alliance-Boots) and still avoid overpriced transactions, unforeseen restructuring bottlenecks, and outrunning its own capabilities?

The private equity industry is changing too. For example, Blackstone, a leading player, launched an IPO in June, allowing the general public to buy a stake in the management company and giving its principals the chance to cash out. Along the way it created a somewhat puzzling structure of a listed public company that itself thrives on secrecy and opportunism. Meanwhile, China recently announced an investment of $3 billion of its massive foreign exchange reserves in Blackstone. A unit of the Chinese government has become a non-voting principal of the firm itself, while not investing in the funds that the firm manages. There may be more to come. To some observers, the “greater fool theory” suggests that opening ownership to outsiders may signal a turn in the cycle.

For now, at least, it seems to be smooth sailing, and private equity deal volume continues at a blistering pace. But, of course, the global economic environment has been extraordinarily benign. A global recession on the order of the early 1980s and early 1990s, or a persistent spike in real interest rates, could easily end in tears for private equity firms, their investors, and some of their debt-holders, as it did after the last two booms. Bubbles are hard to detect in advance. In the end, financial historians may find there was nothing “magic” in the private equity boom after all. Rather, it may be that it was just a product of the times and the free market performing its function.

Ingo Walter is Seymour Milstein Professor of Finance, Corporate Governance, and Ethics at NYU Stern.

A version of this article was published in the June/July 2007 issue of UBS’ staff magazine in Zurich. It represents the views of Professor Walter, and not of UBS.

|

![]()