With each passing year, 401(k) plans become more central to the retirement plans of American workers.

Are companies offering their employees the best possible choice of investment options?

By Edwin Elton, Martin J. Gruber, and Christopher R. Blake

he US system of saving for retirement has been transformed in recent decades. Companies have moved away from offering defined-benefit plans and instead are increasingly offering defined-contribution plans like 401(k). Today, more than one third of all US workers are enrolled in 401(k) plans, which collectively hold more than one trillion dollars in assets.

he US system of saving for retirement has been transformed in recent decades. Companies have moved away from offering defined-benefit plans and instead are increasingly offering defined-contribution plans like 401(k). Today, more than one third of all US workers are enrolled in 401(k) plans, which collectively hold more than one trillion dollars in assets.

The value of any 401(k) pension plan to any participant is determined by two factors: the set of investment choices plan administrators choose to offer to participants; and the set of investments participants choose. While a large amount of research has focused on participants’ investment behavior, none has examined the way in which the choice of investments offered affect the ability of plan participants to construct desirable portfolios. The lack of research in this area is odd, given that an investor faced with an inappropriate set of choices cannot construct an efficient portfolio.

The value of any 401(k) pension plan to any participant is determined by two factors: the set of investment choices plan administrators choose to offer to participants; and the set of investments participants choose. While a large amount of research has focused on participants’ investment behavior, none has examined the way in which the choice of investments offered affect the ability of plan participants to construct desirable portfolios. The lack of research in this area is odd, given that an investor faced with an inappropriate set of choices cannot construct an efficient portfolio.

There are two ways that the choices offered can be inappropriate. A company can offer an insufficient number and type of choices to allow the construction of desirable portfolios. And it can offer poor-performing investment choices of any given type. In theory, the first problem could be alleviated if employees hold funds outside the plan. But for more than 60 percent of plan participants, the 401(k) investments are their sole financial assets. And even for participants who hold other financial assets, 401(k) plans are likely to be the bulk of their savings.

In the best-case scenario, a company should offer a sufficient set of investment alternatives so that the investor can construct the same efficient frontier – a balance between reward and risk – that he or she would obtain if there were choices from a reasonable set of alternatives. We set out to examine how well companies are doing in trying to meet that objective by gathering data, constructing a series of tests, and looking at how a variety of factors – from the use of company stock in 401(k) plans to the hiring of outside consultants – affect performance.

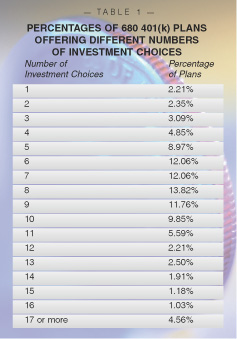

he 401(k) data we examined was provided by Moody’s Investor Services, which surveys pension plans offered by both for-profit and non-profit entities. We identified 680 401(k) plans that offered their participants publicly available mutual funds. Of those, 417 hold mutual funds with at least five years of monthly total returns. For each of these plans, we collected data on the returns, names, and characteristics of the mutual funds offered. Table 1 shows the number of distinct investment choices offered by the plans. The median number of offerings was eight, approximately 12 percent of the plans offered four or fewer investment choices, and about 11 percent offered 13 or more investment alternatives. The most common investment choice (offered by 97.4 percent of plans) was a domestic equity fund, followed by an alternative such as a guaranteed investment contract or money market fund (86.8 percent). Other common offerings were domestic bond funds (71.5 percent), domestic mixed bond and stock funds (80.6 percent), and international bond and/or stock funds (75.1 percent). Finally, 22.9 percent of the 401(k) plans offered company stock as an alternative for their participants.

he 401(k) data we examined was provided by Moody’s Investor Services, which surveys pension plans offered by both for-profit and non-profit entities. We identified 680 401(k) plans that offered their participants publicly available mutual funds. Of those, 417 hold mutual funds with at least five years of monthly total returns. For each of these plans, we collected data on the returns, names, and characteristics of the mutual funds offered. Table 1 shows the number of distinct investment choices offered by the plans. The median number of offerings was eight, approximately 12 percent of the plans offered four or fewer investment choices, and about 11 percent offered 13 or more investment alternatives. The most common investment choice (offered by 97.4 percent of plans) was a domestic equity fund, followed by an alternative such as a guaranteed investment contract or money market fund (86.8 percent). Other common offerings were domestic bond funds (71.5 percent), domestic mixed bond and stock funds (80.6 percent), and international bond and/or stock funds (75.1 percent). Finally, 22.9 percent of the 401(k) plans offered company stock as an alternative for their participants.

Adequate Choices?

In order to determine if 401(k) plans were offering their participants appropriate investment choices, we needed to hypothesize an adequate set of alternative investment choices. To do so, we drew on the field of financial economics, where extensive literature discusses indexes that are necessary and sufficient to capture the relevant return characteristics for a range of investment choices. For common stocks, we used four indexes of small and large value and small and large growth as advocated by economists Eugene Fama and Ken French. All four indexes were taken from Wilshire Associates. For bonds, we combined a general bond index, including governments and corporates (the Lehman US Government/Credit index for the general bond index), and a mortgage-backed index (Lehman Fixed-Rate Mortgage-Backed Securities index). In addition, we used the Credit Suisse First Boston High-Yield index for the high-yield bond index. We also included the Salomon Non-US-Dollar World Government Bond index for international bonds and the MSCI EAFE index for international stocks. Since returns on all mutual funds are computed after expenses, we deducted expenses from each of our indexes. We refer to these eight indexes as “Research-Based,” or RB indexes.

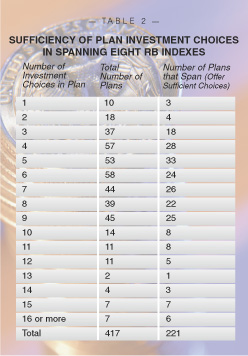

To examine whether the choices given investors allow construction of an efficient frontier similar to that obtained by the eight RB indexes, we drew from the literature on spanning tests. These types of tests let us know whether, given a riskless rate, a particular set of benchmark assets is sufficient to generate the efficient frontier, or whether including members of a second set of assets would improve the efficient frontier at a statistically significant level. In our spanning test, the benchmark assets were chosen from the mutual funds offered by any plan, while the eight RB indexes were the non-benchmark assets. The results of the tests are shown in Table 2. Plans holding four or fewer funds rarely offered a set of funds that span the eight RB indexes. For plans holding six or more funds, we found that about 60 percent of the plans offered investment choices that span the relevant space for investors. Of course, the glass was also half empty: 40 percent of the plans leave investors unsatisfied. Finally, it is not until plans offered 14 or more investment choices that virtually all plans offered investment choices that span the space investors should be interested in. Of the 417 plans, only 53 percent spanned the space obtainable from the eight RB indexes.

To examine whether the choices given investors allow construction of an efficient frontier similar to that obtained by the eight RB indexes, we drew from the literature on spanning tests. These types of tests let us know whether, given a riskless rate, a particular set of benchmark assets is sufficient to generate the efficient frontier, or whether including members of a second set of assets would improve the efficient frontier at a statistically significant level. In our spanning test, the benchmark assets were chosen from the mutual funds offered by any plan, while the eight RB indexes were the non-benchmark assets. The results of the tests are shown in Table 2. Plans holding four or fewer funds rarely offered a set of funds that span the eight RB indexes. For plans holding six or more funds, we found that about 60 percent of the plans offered investment choices that span the relevant space for investors. Of course, the glass was also half empty: 40 percent of the plans leave investors unsatisfied. Finally, it is not until plans offered 14 or more investment choices that virtually all plans offered investment choices that span the space investors should be interested in. Of the 417 plans, only 53 percent spanned the space obtainable from the eight RB indexes.

Does this lack of choice affect returns? Yes. For the 249 plans that do not span the space, to have the same Sharpe ratio – a reward-to-variability ratio – as the optimum portfolio comprising the eight RB indexes, average return would have to increase by 2.18 percent per year. Thus, investors in 401(k) plans were sacrificing significant return because plan administrators offered an incomplete set of investment alternatives.

Adjusting for Risk

We also wondered whether management was selecting individual mutual funds that outperform random selection from similar types of funds. To determine this, we constructed a model to measure performance. Mutual funds were divided into three types – stock, bond, and international – and their returns were compared with relevant indexes. We computed alphas – a measure of how the fund performs independent of the market – for 27 months following the date of our sample. The overwhelming evidence is that alpha is on average negative for mutual funds. Thus a negative alpha for the mutual funds offered by 401(k) plans would not indicate that the manager of these plans selected funds that performed more poorly than random selection. To ascertain whether management was doing a good job of selecting funds, we subtracted from the alpha of each chosen fund the average alpha from a randomly selected sample of funds from the same category. We labeled this difference the “differential” alpha. We found that although 401(k) plan administrators selected funds with negative alpha, they selected funds that had smaller negative alphas than random selection. However, the average differential alpha was significantly different from zero for only one category – bond funds. Our results also showed that the difference in performance is due to the managers choosing funds with lower expense ratios.

We know that there is a tendency for plan participants to place a disproportionate fraction of their plan assets in company stock. On average, we found that companies offering company stock as an investment choice offered the same number of mutual fund choices as those that do not. Our analysis also showed that only four more firms spanned the space when company stock was included. Furthermore, although the inclusion of company stock led to risk increasing, the risk was more than offset by an increase in return. Considering the 401(k) plan as the participant’s sole financial asset, the inclusion of company stock in a plan seems to neither improve nor harm the investor making intelligent 401(k) plan choices. However, since a plan participant’s labor income may be highly correlated with the performance of the company stock, a portfolio including labor income, 401(k) mutual funds and the company stock may be significantly more risky than a portfolio excluding the company stock.

We know that there is a tendency for plan participants to place a disproportionate fraction of their plan assets in company stock. On average, we found that companies offering company stock as an investment choice offered the same number of mutual fund choices as those that do not. Our analysis also showed that only four more firms spanned the space when company stock was included. Furthermore, although the inclusion of company stock led to risk increasing, the risk was more than offset by an increase in return. Considering the 401(k) plan as the participant’s sole financial asset, the inclusion of company stock in a plan seems to neither improve nor harm the investor making intelligent 401(k) plan choices. However, since a plan participant’s labor income may be highly correlated with the performance of the company stock, a portfolio including labor income, 401(k) mutual funds and the company stock may be significantly more risky than a portfolio excluding the company stock.

Size Matters

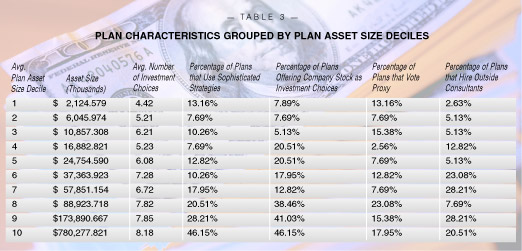

In our sample, there was a wide variation in the size of the plans. The average plan in the top 10 percent was over 300 times as large as the average plan in the lower 10 percent. Many investors tend to think that bigger is better. We set out to examine whether this might be the case when it comes to 401(k) plans. When we ran our tests, it turned out there was a clear and statistically significant relationship between plan size and the number of investment choices offered. A higher percentage of larger plans also hired outside consultants and engaged in more sophisticated investment strategies than did smaller ones. Not surprisingly, large plans showed a stronger tendency to include company stock in the plan than did small plans. But it turns out that hiring outside consultants may not necessarily result in an improvement of offerings. We found that the use of outside consultants or sophisticated strategies did not result in a significantly greater likelihood of the company offering fund choices that spanned the investment space.

To a degree, the 401(k) revolution represents something of an experiment. For the first time, millions of workers have been asked to direct and manage their own retirement savings. This places the burden of making smart decisions about whether to invest, how much to invest, and what to invest in, squarely on the shoulders of employees. And every year, companies devote significant resources to make sure employees have the necessary information to make appropriate decisions. But our research suggests that for 401(k) plans to live up to their full potential, employers have to devote time, attention, and resources to make sure that they are making intelligent decisions as well.

Edwin Elton and Martin J. Gruber are Nomura Professors of Finance at NYU Stern. Christopher Blake is professor of finance at Fordham University.

This article, the first to examine the reasonable choices offered to investors, is based on the authors’ upcoming article in the Journal of Public Economics.

![]()